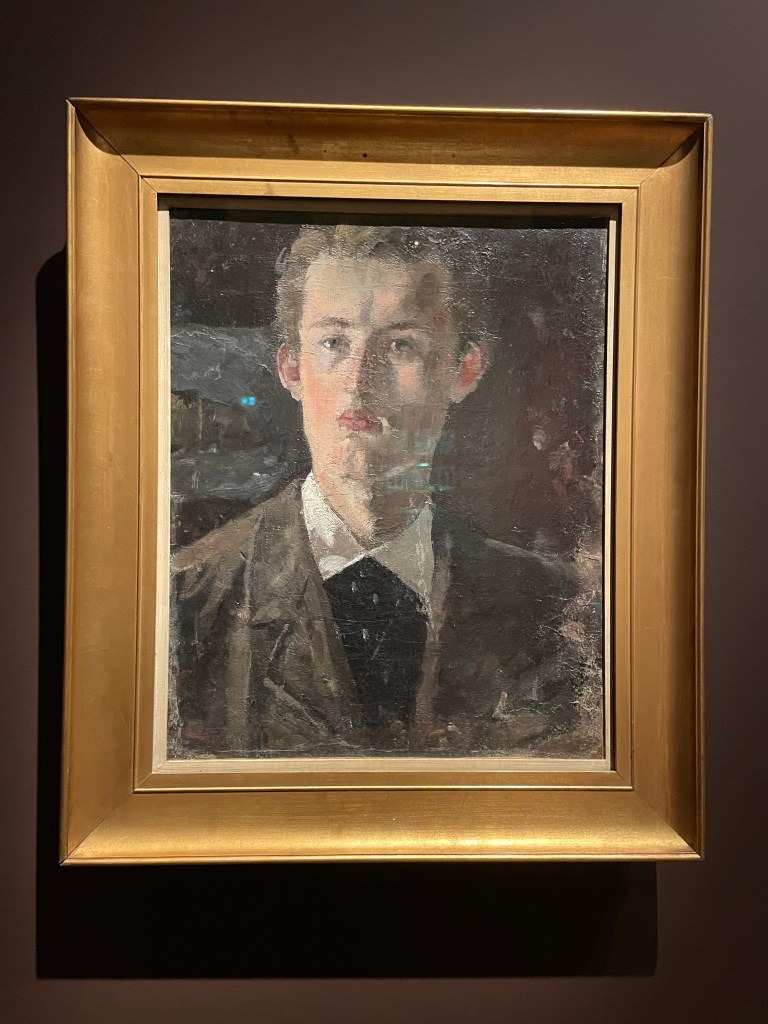

Colour! Yes, serious colour and, to my mind, a speediness of thought and hand in the creation of many of these portraits. I enjoyed the dribbles, splodges and daubs of hasty painting, as if he were in a great hurry to capture the subject in front of him and then get on with something else. Above: Torvald Stang, a friend, and self portrait of Munch.

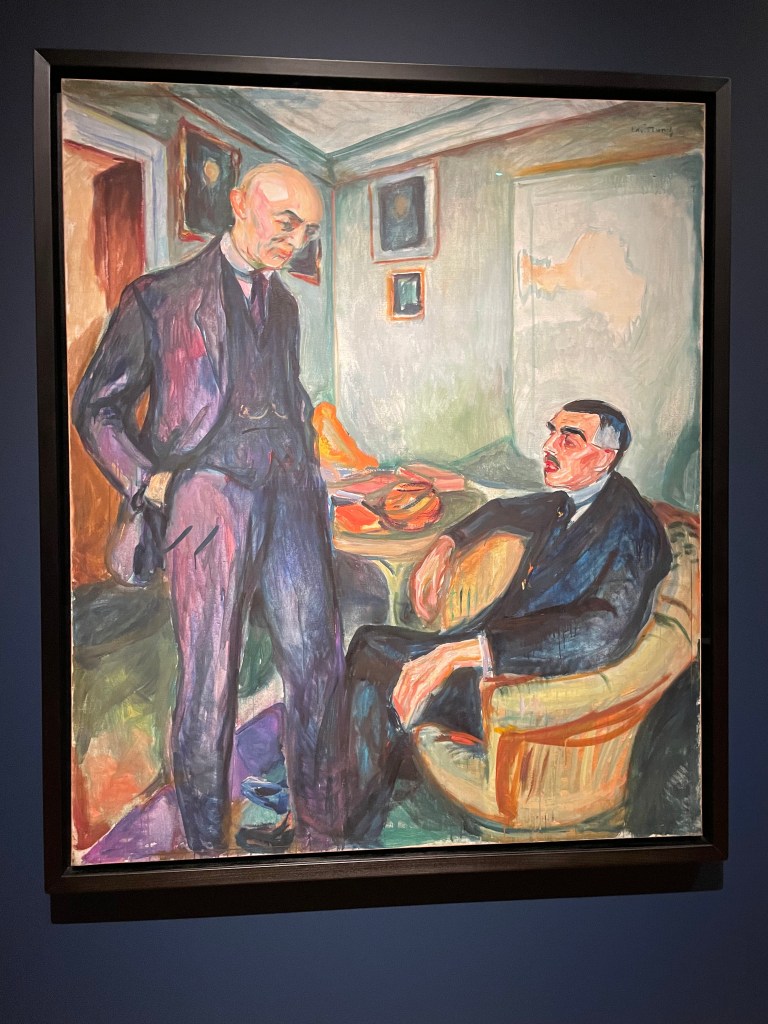

Munch was clearly very fond of his friends and family and painted them with obvious pleasure. And he liked depicting them in pairs. This is very much a theme. People with a connection occupy the same space and, again, were painted at much the same pace with an equal distribution of attention to detail. Above: Lucien Dedichen and Jappe Nilssen – friends from Munch’s student days. And on the right are sisters Olga and Rosa Meissner, professional models.

There’s an overwhelming tenderness to many of the paintings and, in some cases, they might not seem finished. But, to Munch, he had provided quite enough detail in the face and the rest of the figure can be filled in by the viewer’s eye. Above: Inger, Munch’s younger sister, looking charming in sunshine and Inger Barth, a friend. This work was confiscated in 1937 when it was among the works declared to be ‘degenerate’ by the National Socialist government.

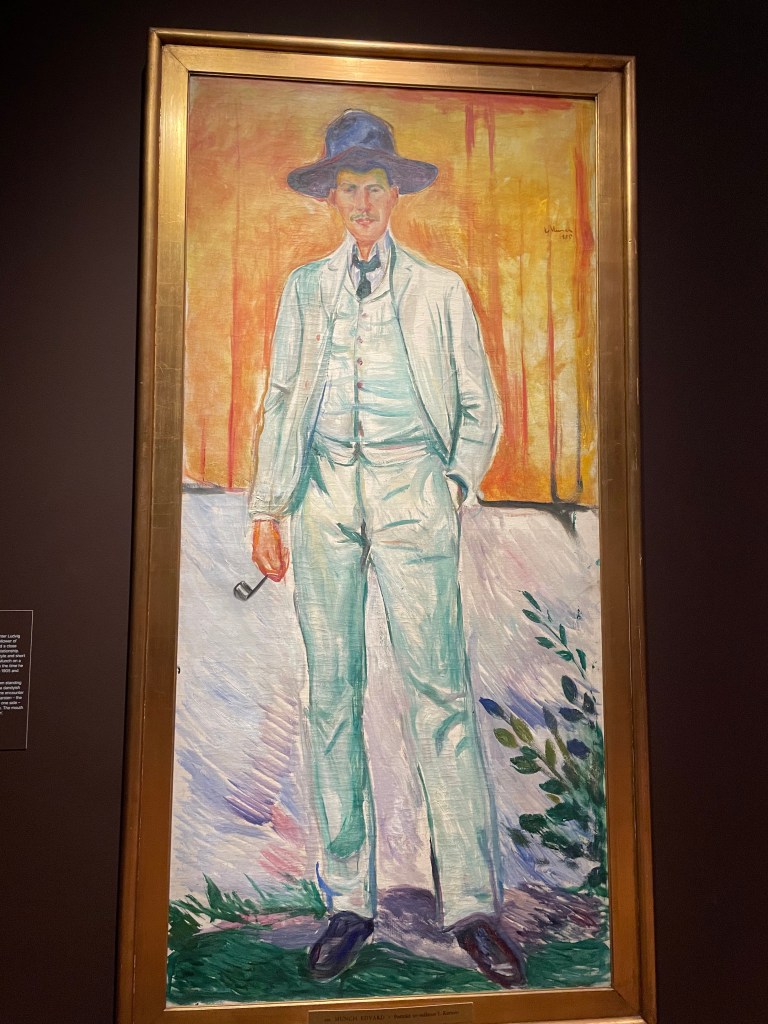

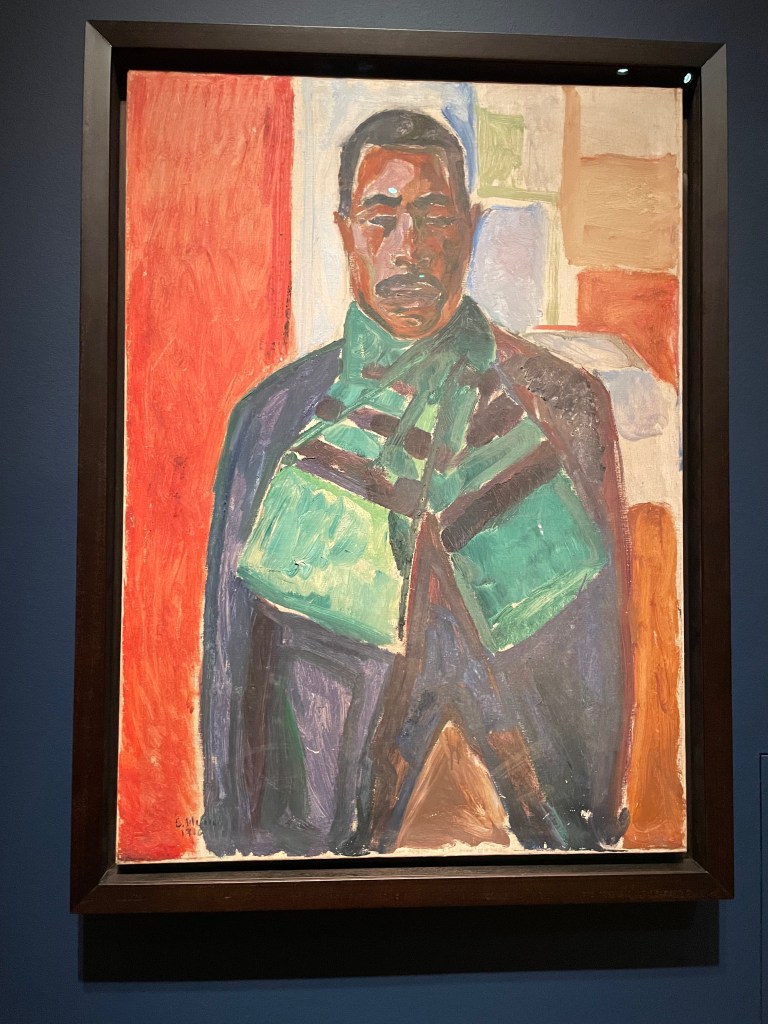

What’s absolutlely apparent is the free-flowing style we recognise from his later, angst-riven work. I like the direct gaze of his subjects. It looks as though they must have been deep in conversation when the portrait was being made and the affection between sitter and artist is very apparent. Above: the Norwegian colourist painter Ludvig Karsten in a ‘dandyish’ pose, August Strindberg, the playwright, and Sultan Abdul Karem whom Munch employed.

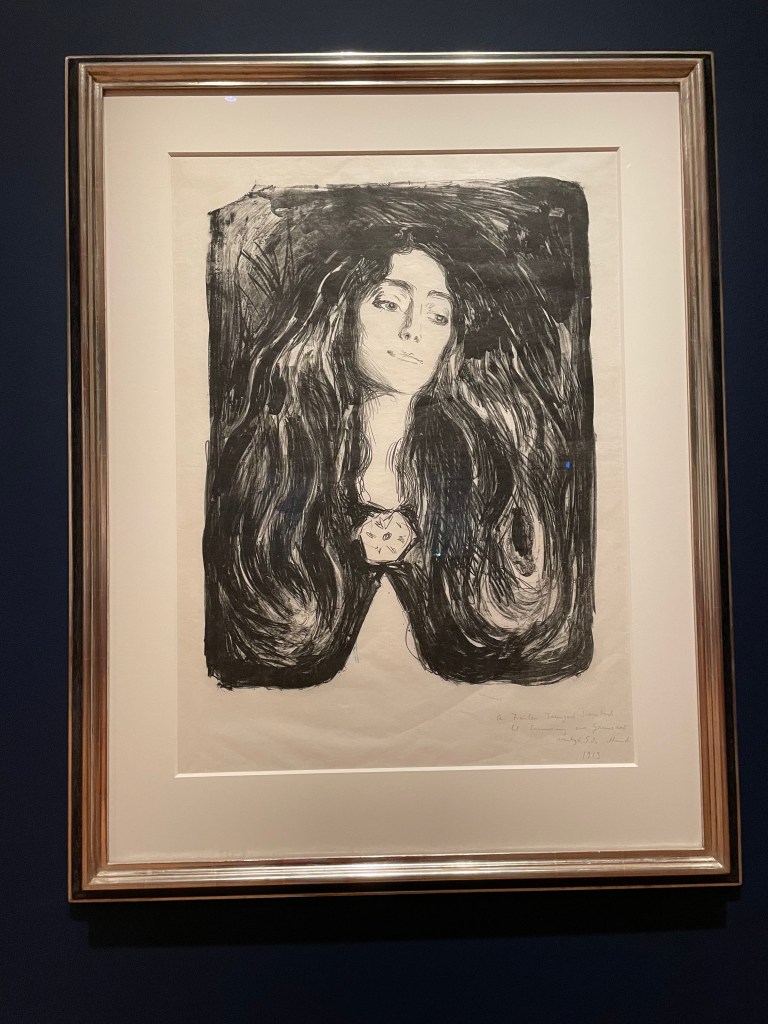

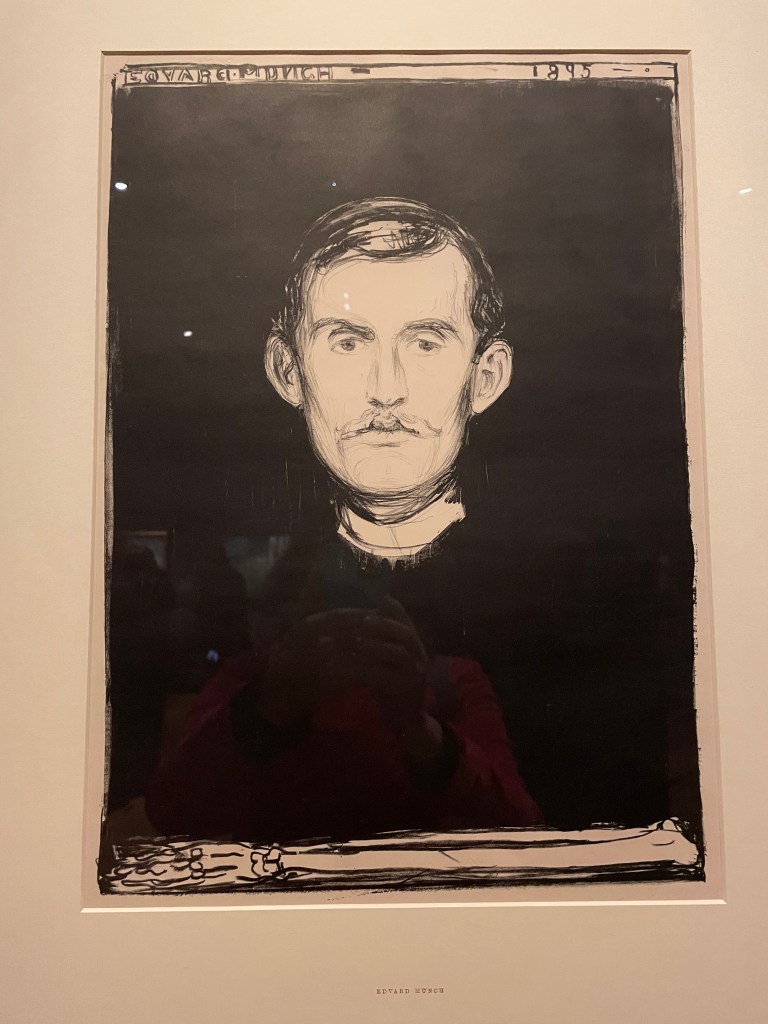

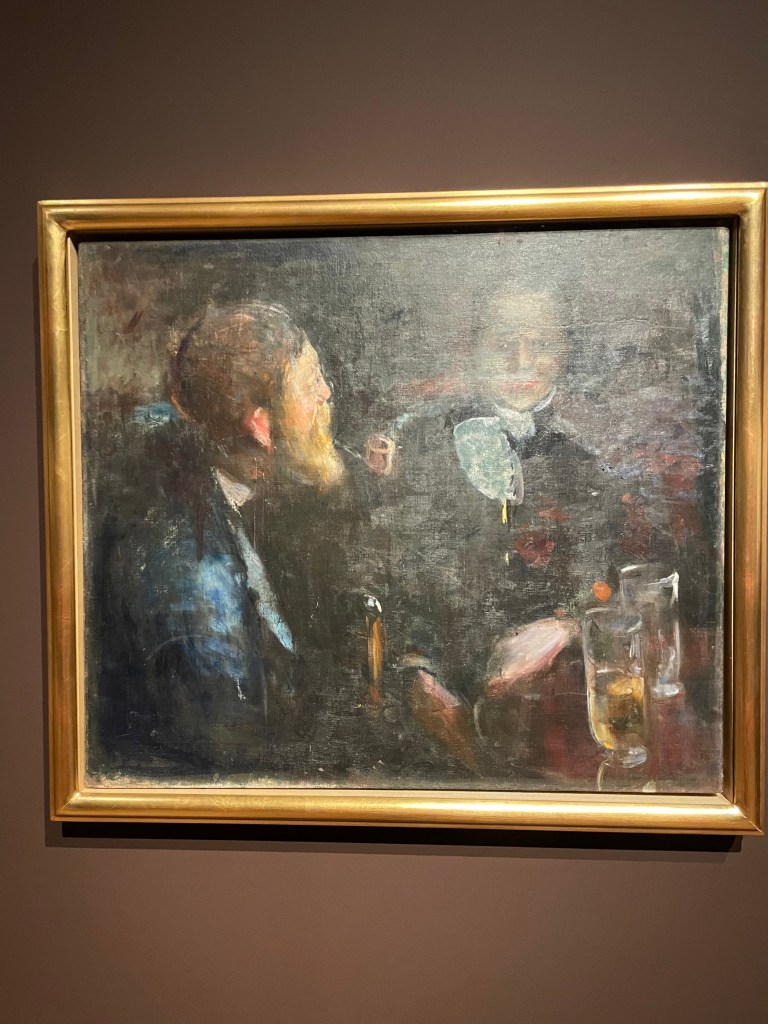

Just a few of the lithographs and black and white portraits (and the very dark one on the right) give a hint of the darkness within. But one comes away from this show in a very uplifted state, pleased to see such great portraiture by one of the 20th century’s finest artists. Above: lithograph portrait of Eva Mudocci, 1902, and self-portrait with skeleton arm, 1895 and on the right Tête à Tête, 1885, showing the painter Karl Jensen-Hjell drinking in the cafe in conversation with woman who might be Inger Munch. Very atmospheric.

Above: a self-portrait and a very tender portrait of Munch’s father, Christian, a military doctor. The show is on at the National Portrait Gallery until 15th June 2025. Well worth it.