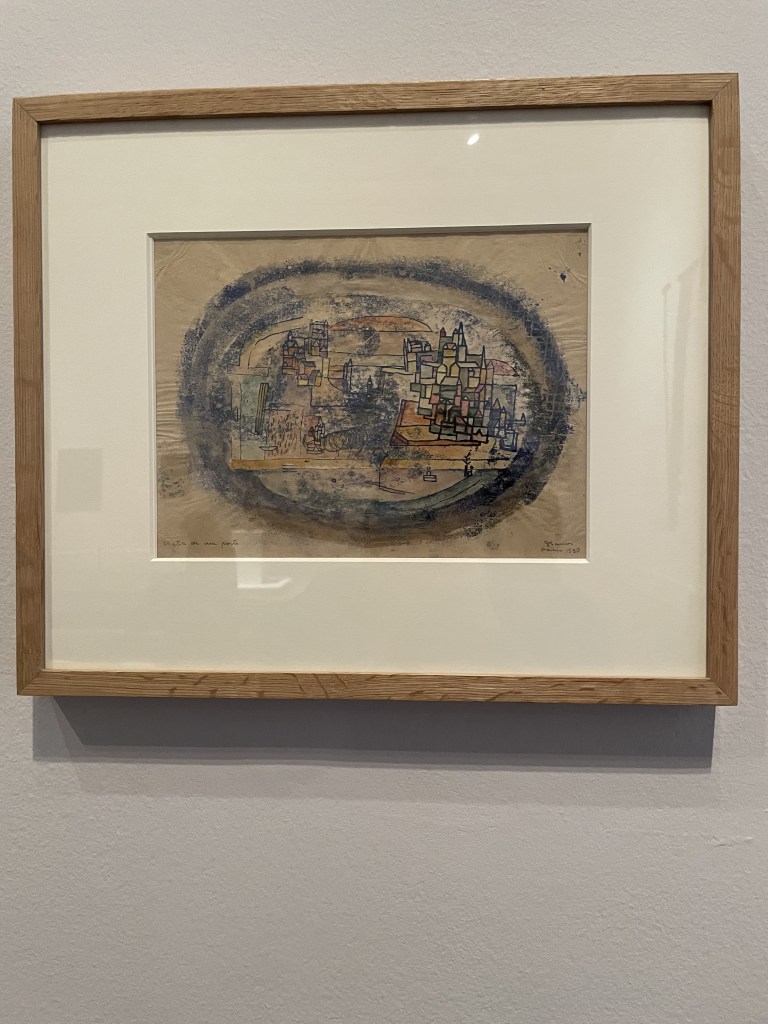

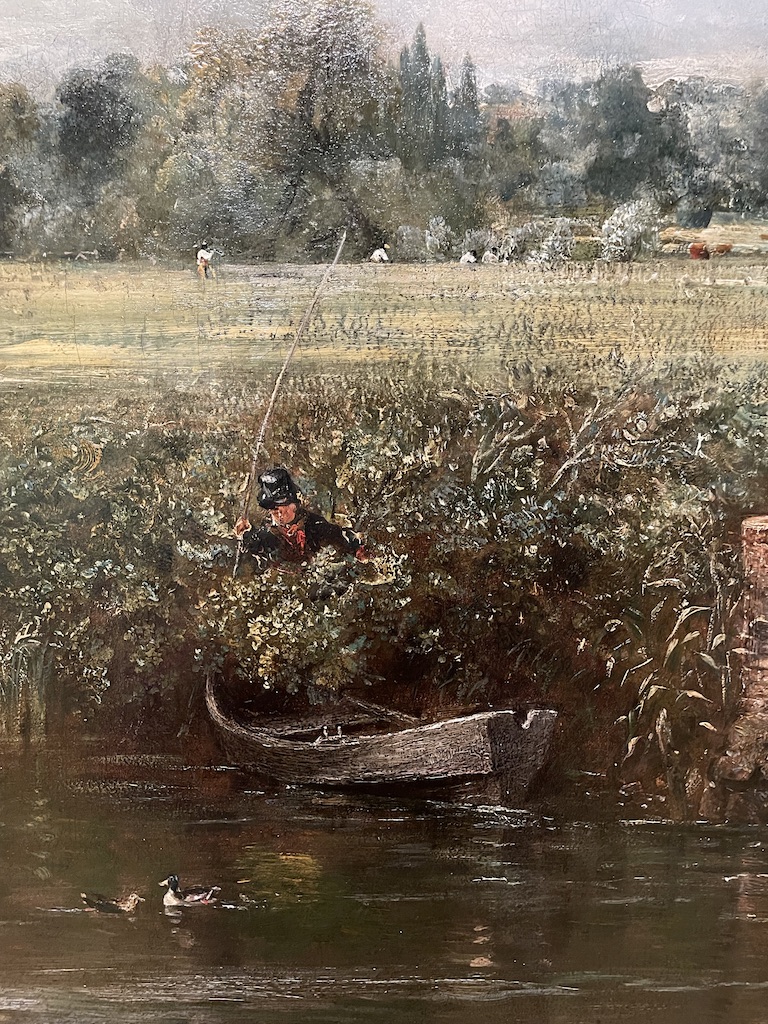

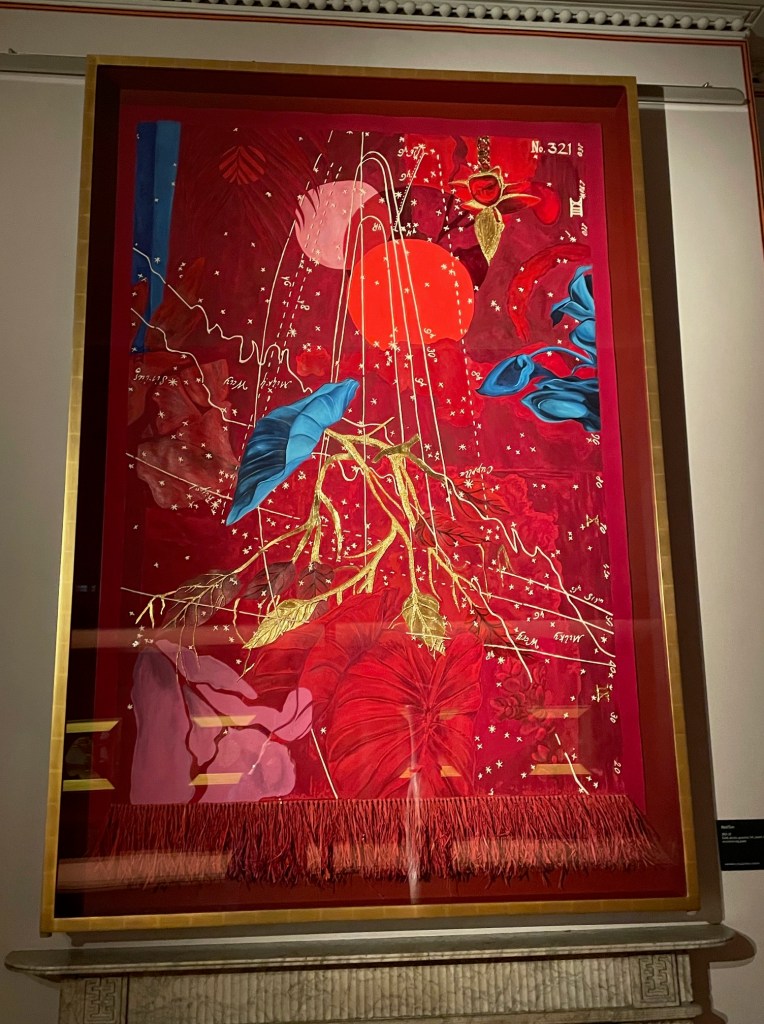

As a keen ‘pond dipper’ I was intrigued by this show and very pleased to see a reference to the Women’s Pond at Kenwood, a place I find very addictive during the summer months, but only once the water has inched its way towards at least 15 degrees and even better when it reaches a balmy 20 degrees. The poster showing Ken Wood suggests the pond nestles beneath high mountains. Hampstead Heath is not that high but I did like romance of the image.

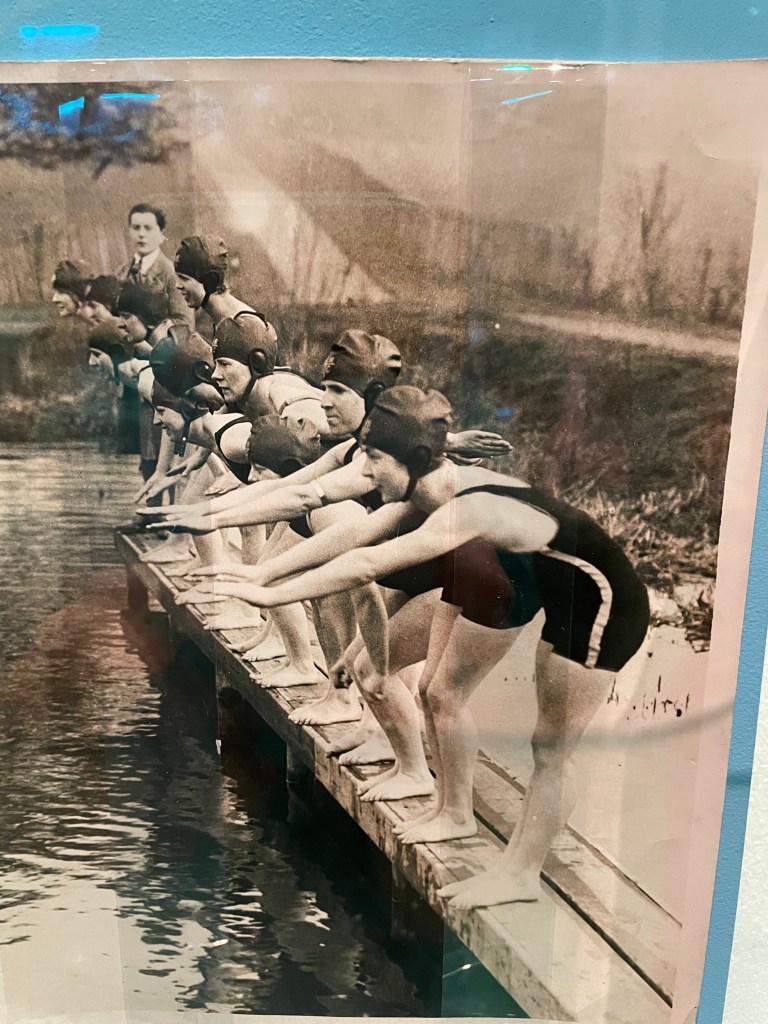

There are a great many swimming costumes on show. I remember my mother describing the indignity of wearing a woollen swimsuit when she was a child in the 1930s. The thing just spread out in the water before slapping back against her body, dragging down to her knees when she emerged from the water covered in embarassment.

But what I’d really hoped to see was the type of swimming costume I wore as a child – blue nylon, ruched by criss-crossed elastic. I have such a strong memory of my swimsuit and the way the little triangles of fabric would fill with water, swell and then gradually empty on emerging from water. Alas, this curious garment was not represented. Instead the star of the show was the red swimsuit worn by Pamela Anderson in Baywatch.

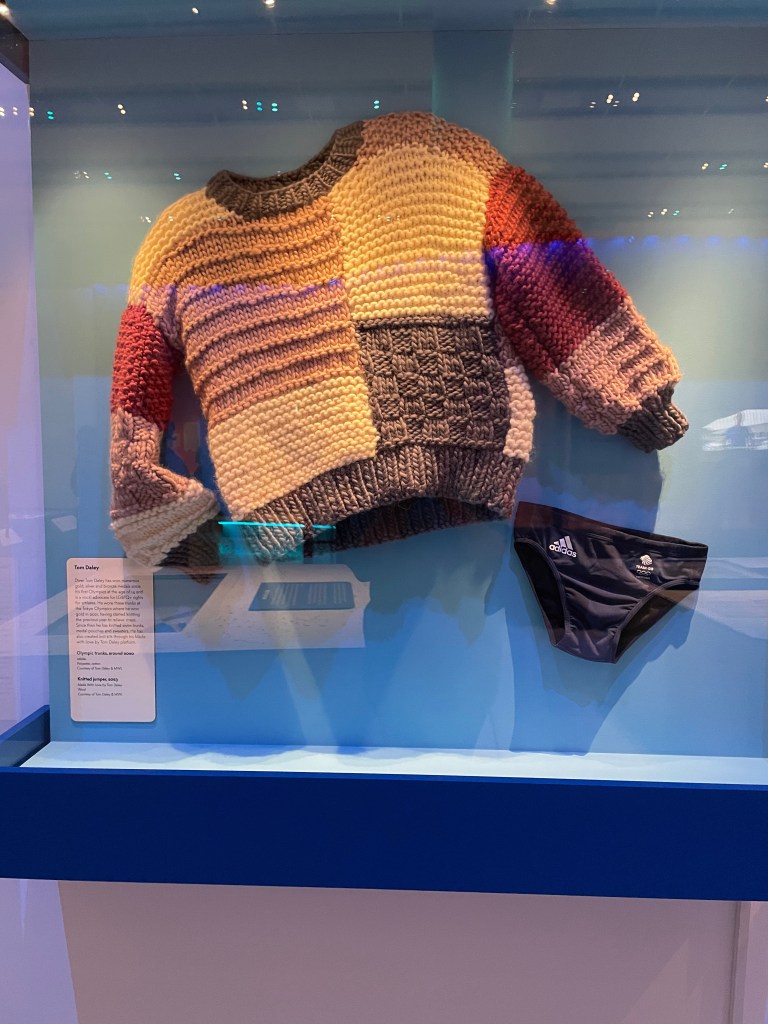

Fun to see the Gold Medal winning diver, Tom Daely’s scanty trunks and also the chunky sweater he knitted to occupy himself waiting for his moment at the Olympics.

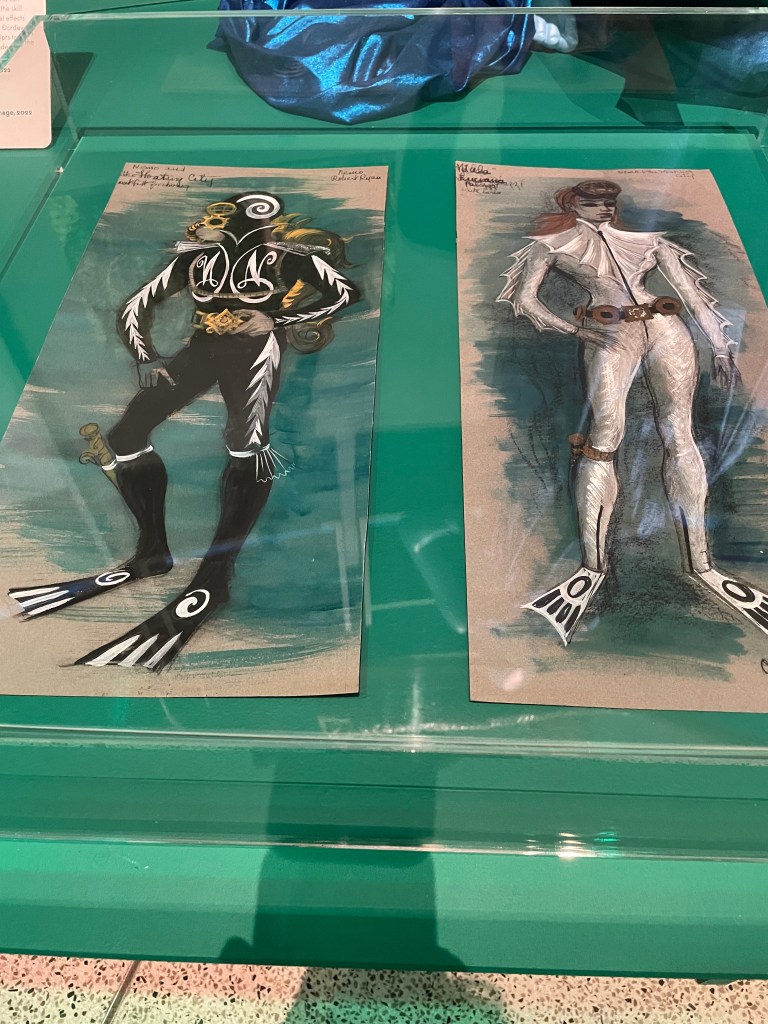

Good to see the costume designs for Captain Nemo and the Underwater City. They wouldn’t look out of place in a ballet.

My takeaway from the exhibition was that something had been missed. Because it was so much about the design of objects used in or near water we didn’t get a feel for the spiritual nature of water and the very human, primal desire to be close to the sea, rivers, ponds or expanses of water. We both fear and revere water. There’s a desire to be near it but not for it to come too close, univited and offend us by flooding our homes or disturbing our travel with dangerous high tides or inundated roads. Perhaps that’s something for a different show.

Splash! is on at the Design Museum until 17th August.