Above is a detail from probably the most famous painting by Joseph Wright, known as Wright of Derby – the town where he was born and worked. The Air Pump shows an audience watching a scientific demonstration. The air is being pumped out of a glass flask and the bird inside is about to suffocate. The girls are clearly distressed, the adults fascinated and the scientist resembles a wizard, in a loose gown, playing God over the life of the hapless bird. There is so much going on in this compelling picture which gives you so many perspectives. But the most striking element is Wright’s ability to capture the lighting of the scene. A single candle, hidden behind a large goblet containing a skull, illuminates the faces and highlights the reactions.

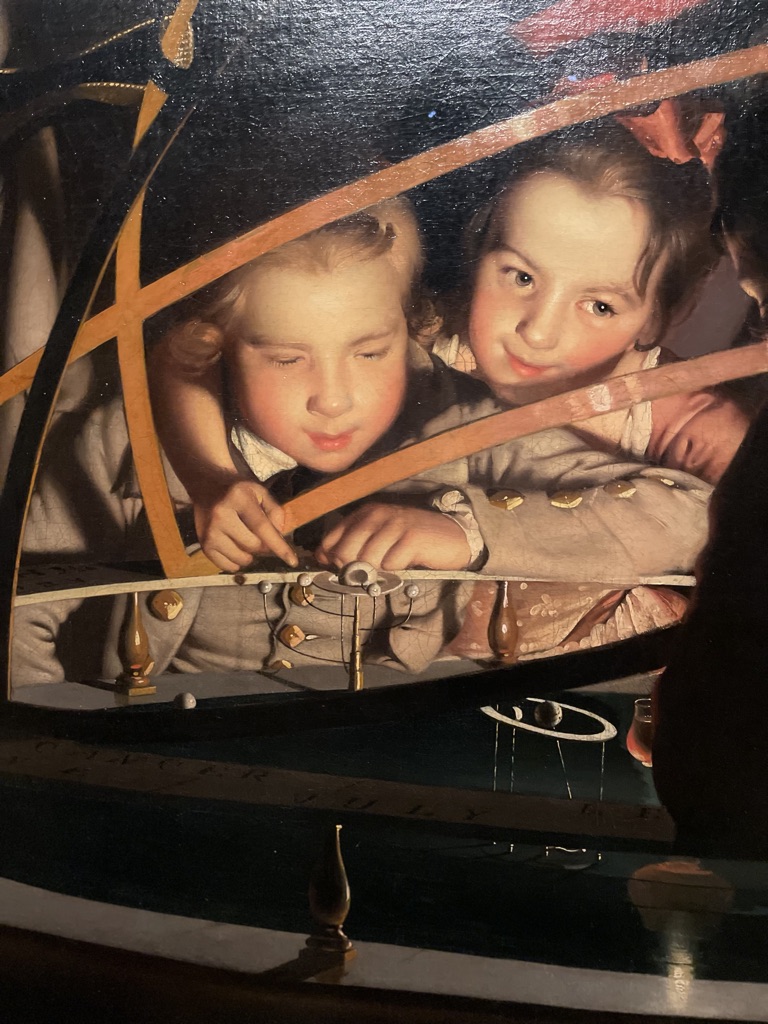

This wonderful exhibition not only brings the best of Joseph Wright’s paintings from the 1760s-70s but also assembles some of the instruments and props which feature in the pictures. For example, below, we see a painting entitled The Orrery which was an extraordinary teaching instrument for demonstrating the movement of the planets and the earth’s place in the heavens. The two boys are transfixed by the tiny orbs which are shown to move around each other.

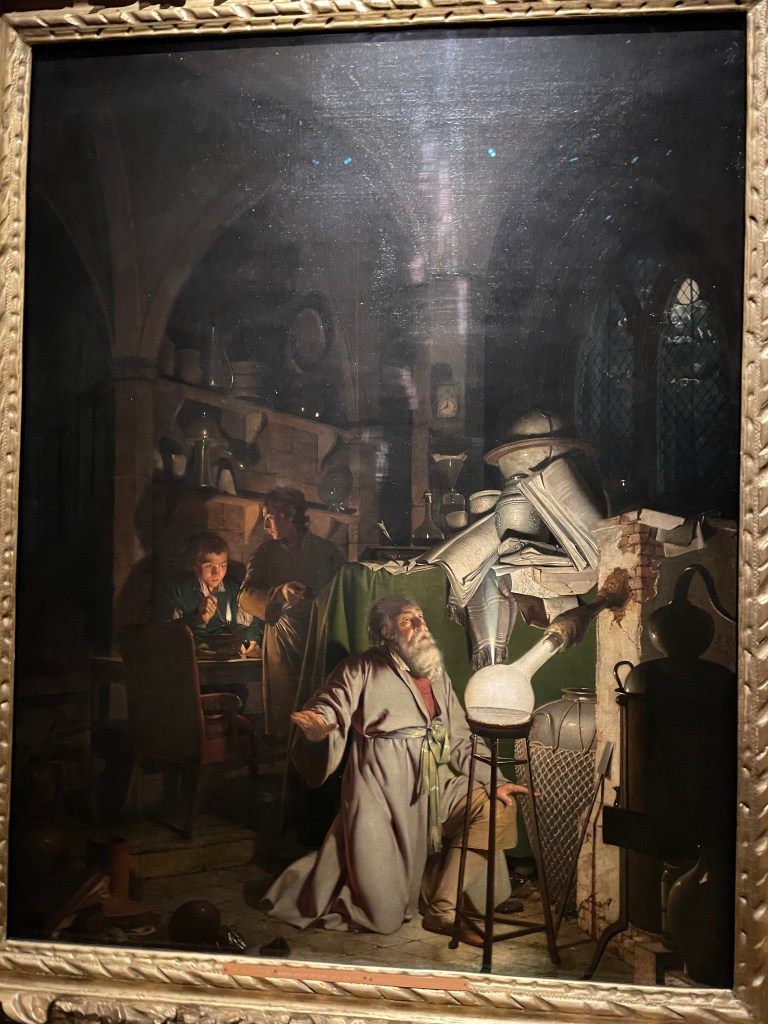

Tenebrism is the word given to the style of painting associated by Italian artist Caravaggio and describes the use of an extreme form of ‘chiaroscuro’ (meaning light and dark). The drama derived from seeing, and not seeing, objects is brilliantly conveyed in these picture. As a viewer you are drawn to the illuminated faces and the expressions responding to the action but then you wonder what is happening in the shadows? Each picture contains so many questions and invites you to puzzle over the subject as you scan the painting absorbing the story.

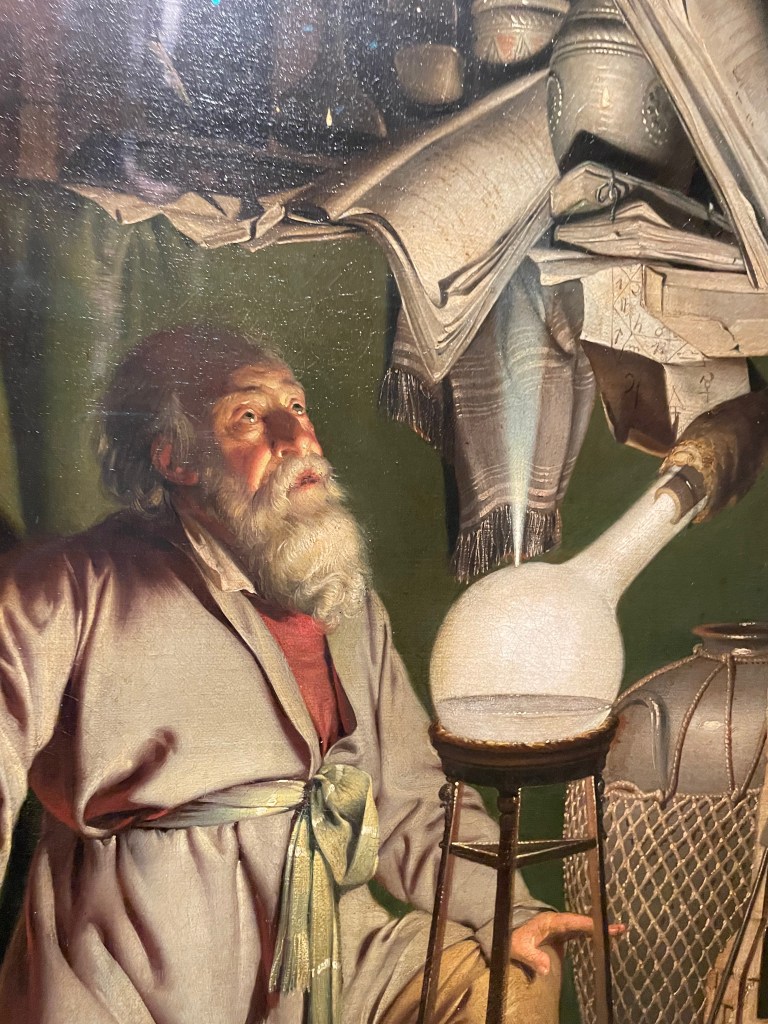

Above is The Alchymist in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and Prays for the Successful Conclusion of his Operation, as was the Custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers. Wow! Quite a title, but what a picture, there’s so much going on. Amazement on the face of the alchemist and bewildered fascination by his helper making notes at the desk by candlelight. And capturing the bright light of phosphorus must have been a huge challenge.

I love this painting of the girl reading the letter. You can’t see the candle but it’s behind the paper, making it transparent, but for the shadowy fold. And is the man leaning over her shoulder about to grab the paper away? What was she reading? Oh, so many questions. This painting is up there with works by Vermeer but with a more rosey hue and earthy atmosphere.

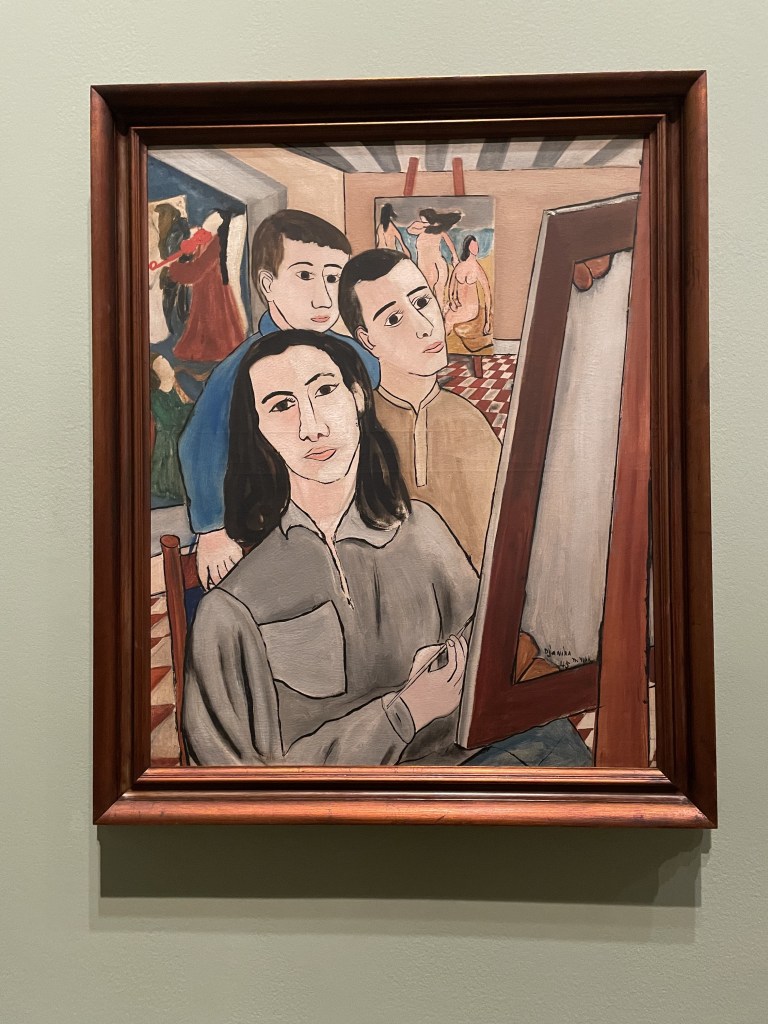

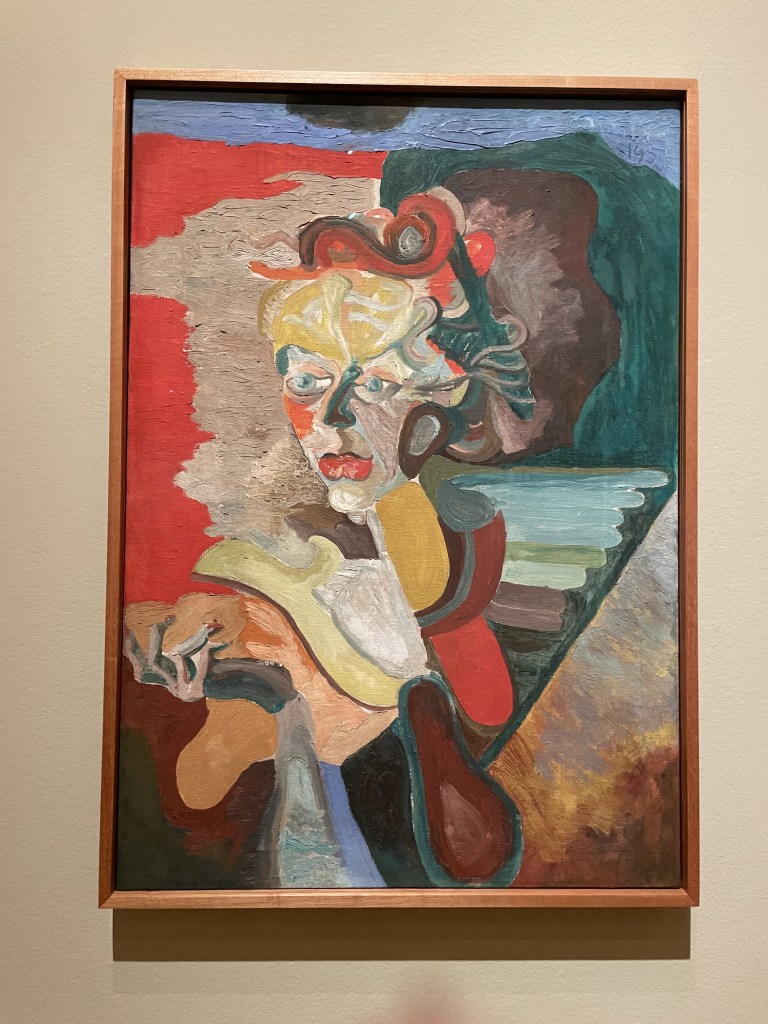

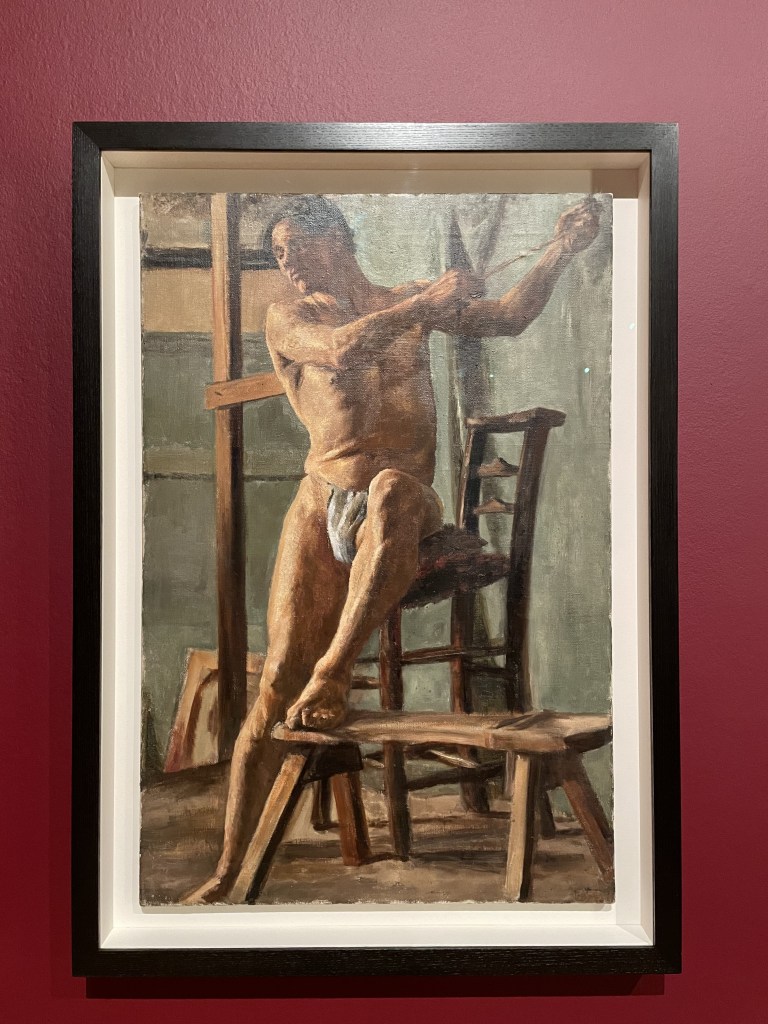

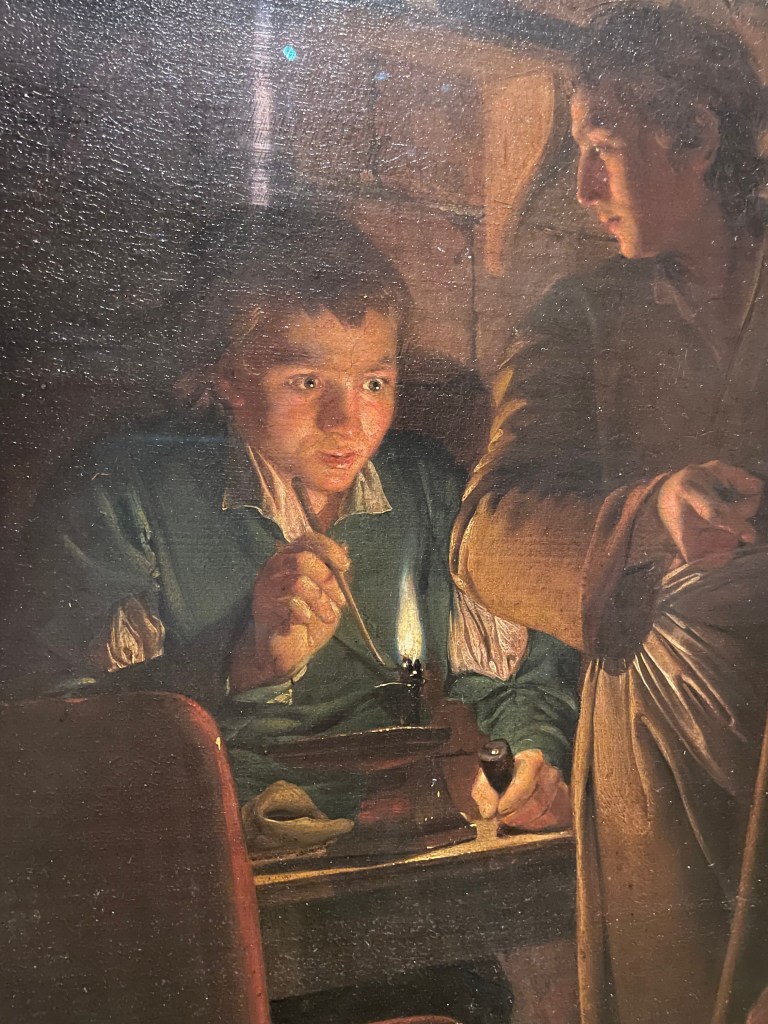

Above are a couple of great examples of ‘tenebrism’ showing not only Wright’s skill at capturing light but depicting the enduring artistic quest to capture form by using light and shadow in the context of the art class.

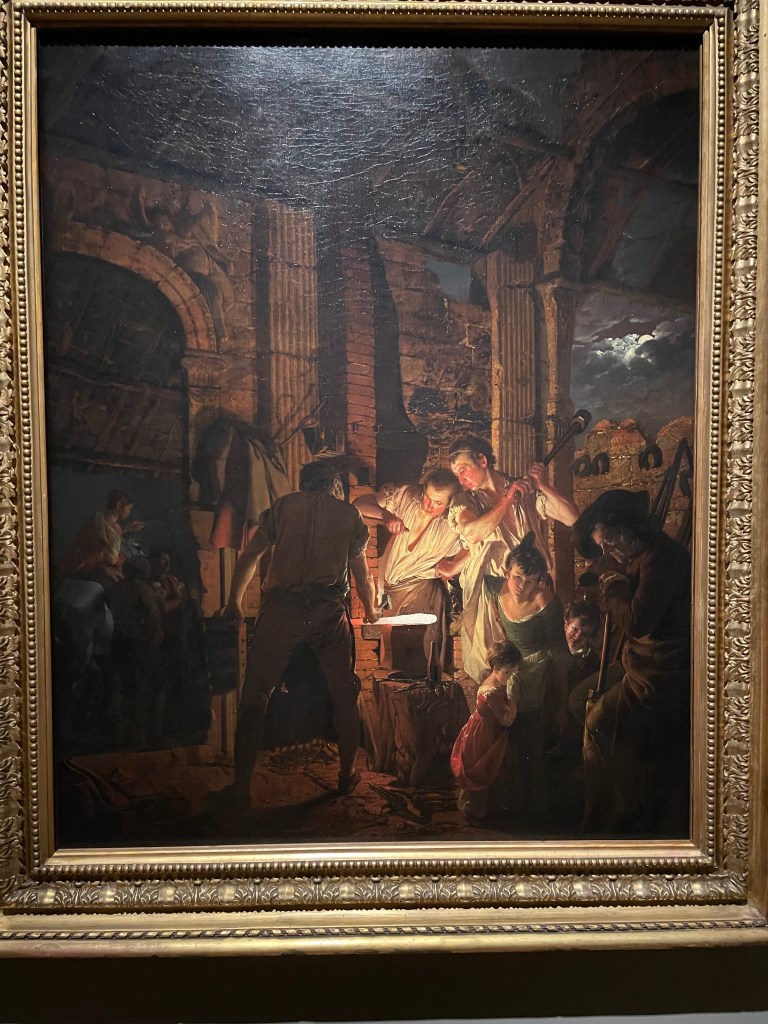

And above is a detail from a painting of two boys fighting. You can see that things are turning violent as one boy’s ear is grabbed and pinched with his assailant in the foreground represented in shadow. And I loved the picture on the right of A Blacksmith’s Shop. Nighttime work, with the moon beyond the clouds and all eyes focused on the action on the anvil. Wonderful.

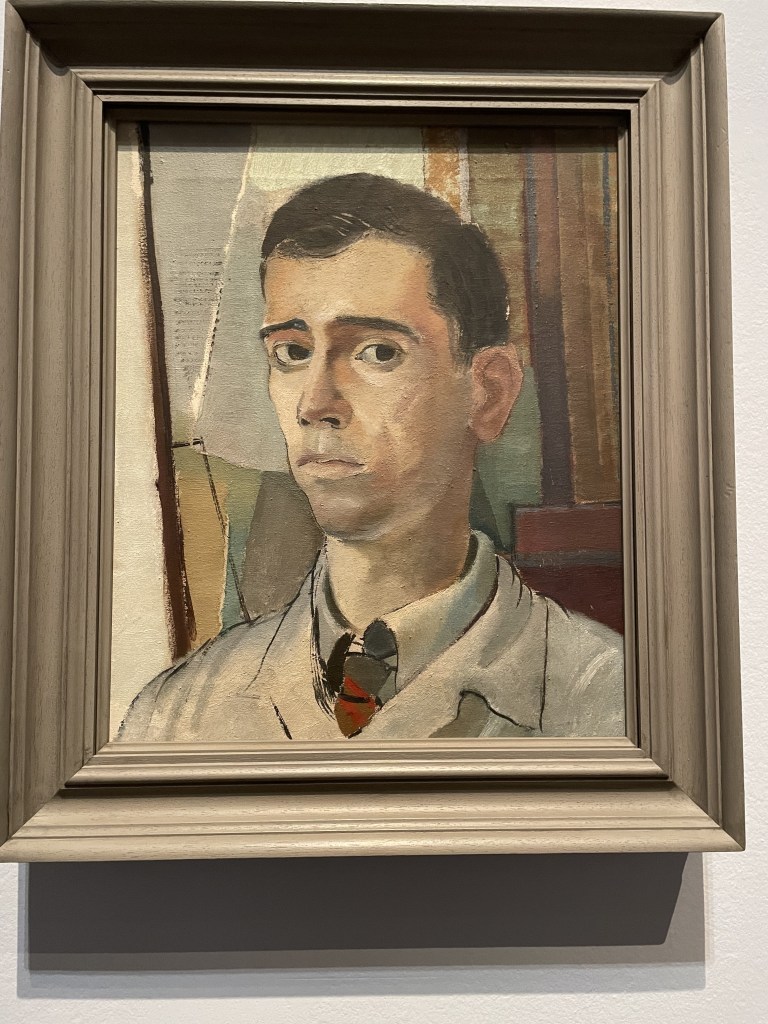

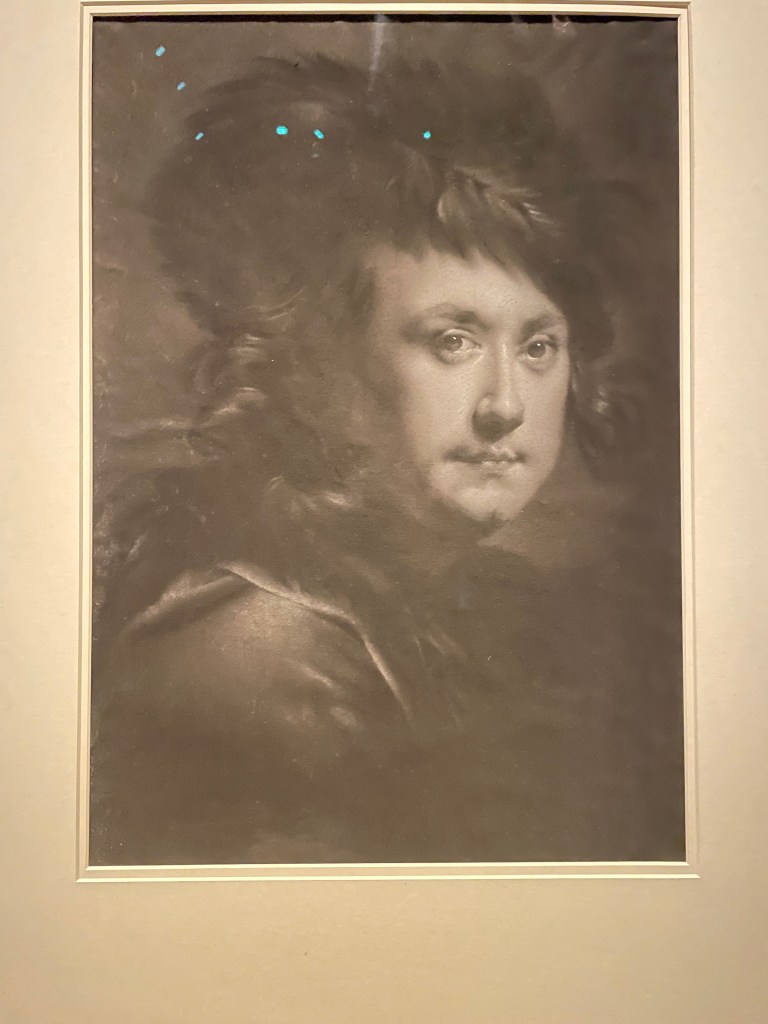

Above is a self-portrait by Joseph Wright of Derby done with pastels early on his career. Clearly he was perfecting his ‘tenebrist’ skills but, quite playfully, representing himself in the style of an ‘Old Master’. What a master of his craft he was. This is a great show. It’s on at the National Gallery until 10th May 2026.