I had no idea what to expect when I attended the press preview for this show. My knowledge of Indian history is scant. For this exhibition we were introduced to the work generated by Benode Behari Mukherjee, his wife, Leela, daughter Mirnalini and students who lived and work an an idyllic-sounding art school established in Santiniketan in 1919. This was a time when Indian artists might look to the West for influence but were determined that their work would be definitively Indian, and reflect their deep-rooted culture.

I was impressed by the variety of work and, at times the visceral nature of the imagery. Above is a water colour sketch on paper by Leela Mukherjee demonstrating the influence of Matisse through bold, vigorous brush strokes.

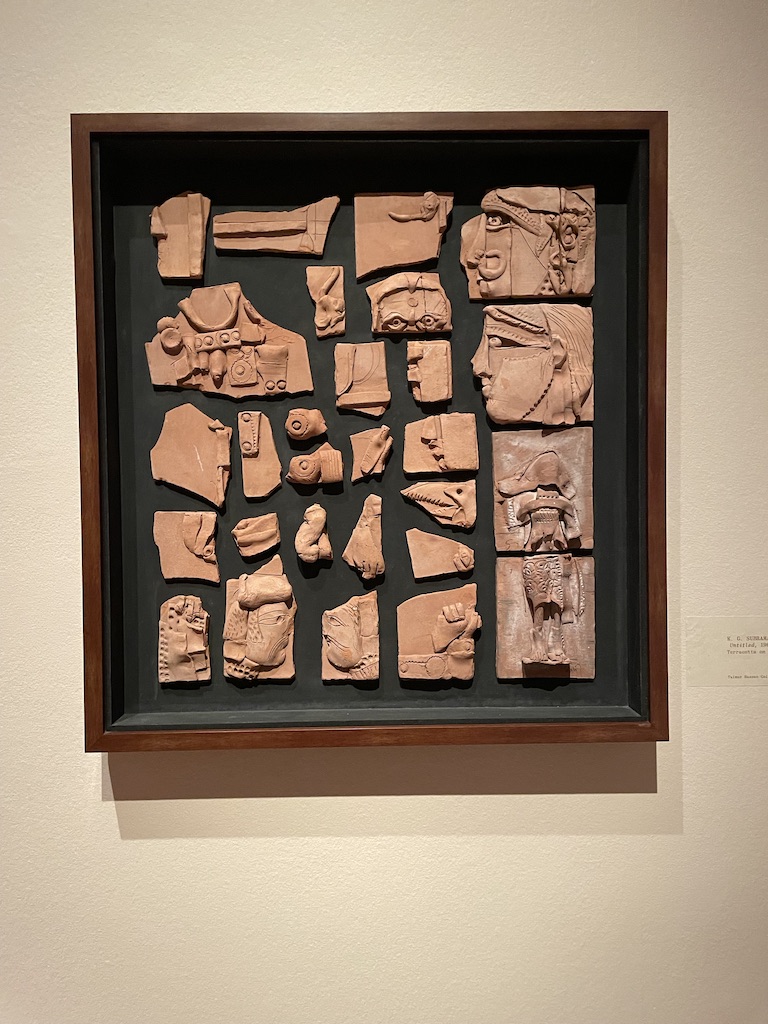

I really liked this trio of work. On the left is a paper collage made with cut outs by Benode Mukherjee. He became blind in his 50s but continued working and teaching. His daughter, Leela, worked closely with him, describing what she could see around them and helping him interpret his art by preparing and cutting up paper for him to collage. He would then, intuitively, ‘feet’ his way into these later works. In the centre is a carved wood mosaic by K G Buramanyan (a student) which relates to a monumental mural commissioned in 1962. The mural stretches some 25 metre and used 13,000 terracotta tiles – examples are shown on the right.

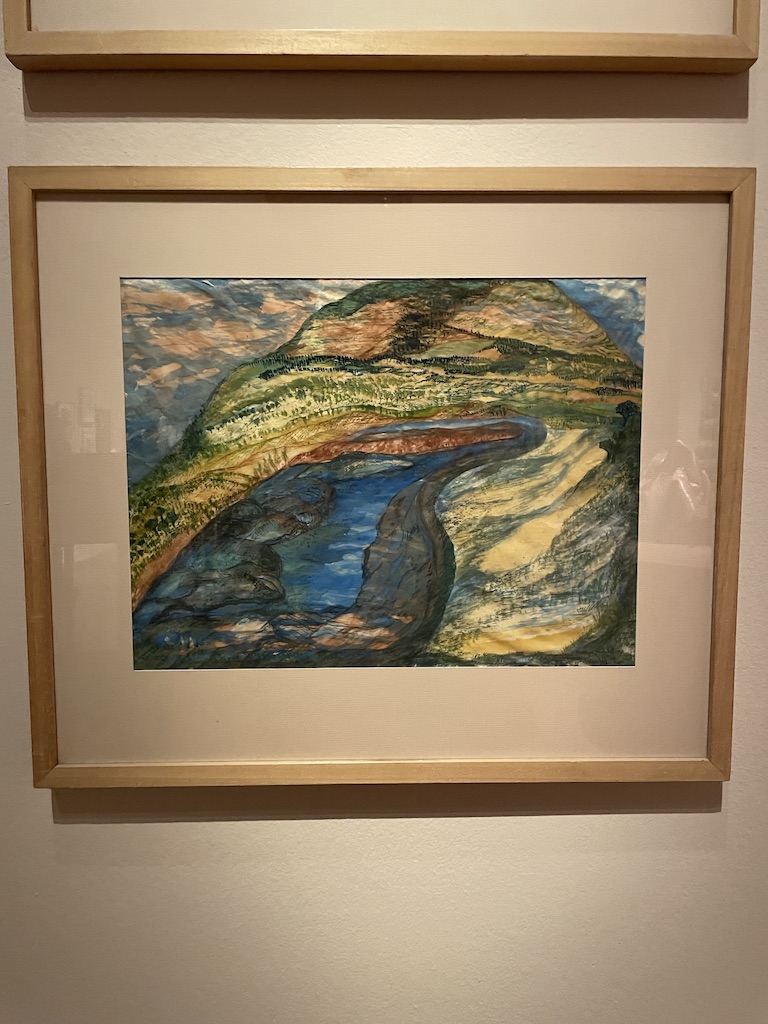

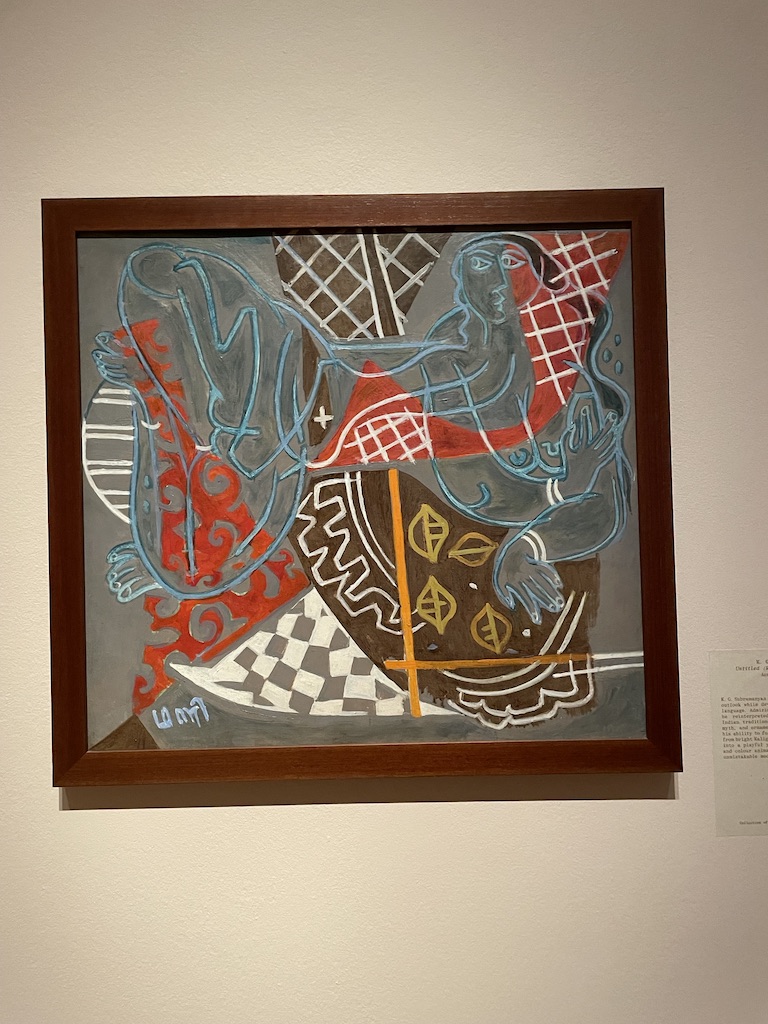

These two paintings caught my eye. On the left is a watercolour by Mrinalini Mukherjee which is like an abstract landscape using great colours. And on the right is a very Matisse and Picasso-inspired ‘Reclining Woman’ by K G Subramanyan.

The sculptures are interesting. On the left is Night Bloom II by Mrinalini Mukherjee, a partly-glazed ceramic made with folds of clay which convey the idea of a woman seated in the lotus position. They clay bears impressions of textiles. And on the right is her intriguing sculpture named Jauba, from 2000 made with hemp and steel.

I found this lithograph, Landscape 1968, by Gulammohammed Sheikh quite threatening with intimations of unsettling goings on. And on the right is an etching entitled Riot from 1871 where the violence is evident.

A very intriguing show. It’s on at the Royal Academy until 24 February 2026.