We take it for granted these days that men and women can forge equally successful careers in art. Four hundred years ago it was a different story. But women still studied art, became proficient at their skill and even earned a living. The curators of this excellent show have found examples of work by over 100 female artists working in Britain from 1520 – 1920 and it’s the most uplifting exhibition.

I really liked this portrait of Messenger Monsey by Mary Black,1737-1814. This is her only known oil painting and it’s so full of character and technical skill. Apparently, Black expected Monsey to pay her £25 for the portrait but her subject objected and suggested that she should not be paid at all for her work, claiming it would damage her reputation and that she might be regarded as a ‘slut’, if she sold her skills. Dear, dear.

This is a tiny self-portrait by Sarah Biffin (1784-1850) who was born without arms or legs. Yet she taught herself to paint, sew and write using her mouth and shoulder. She specialised in portrait miniatures and often signed her work, ‘painted by Miss Biffin Without Hands’.

This is a portrait of Elizabeth Montagu by Frances Reynolds, sister of Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy. Frances was denied the opportunities of her brother and kept house for him in London and learned to paint by making copies of his work. She was a member of the Bluestocking Circle, a group of women writers, artists and intellectuals who met at the house of philanthropist Elizabeth Montagu, the subject of this wonderful painting.

A charming portrait of Miss Helena Beatson made using pastel on paper by Katherine Read 1723-1778, her aunt. Pastels were not rated by the oil painting men of the period but they were easier to obtain and use by women. The young child in the portrait turned out to be a prodigy and was exhibiting at the Society of Artists at the age of eight.

This fascinated me. It’s a self-portrait made entirely from embroidery by Mary Knowles 1733-1807. Queen Charlotte commissioned her to make a portrait of her husband, King George III, you can see she’s working on it. The clever way she uses silks to create the moulding and lively look of the picture is amazing.

Loved the strength of this and the painterly confidence. It’s by Ethel Wright 1855-1939 and a portrait of Una Dugdale Duval who is famous for refusing to promise to obey her husband during their marriage vows in 1913.

These are two paper cutouts, mosaics created by Mrs Delaney 1700-1782, who used collage, based on the Dutch art known as knipkunst, and used fragments of cut paper to depict, with amazing accuracy, examples of plants and flowers. Mrs Delaney was a favourite in the court of King George III and was given an apartment to live in at Windsor Castle.

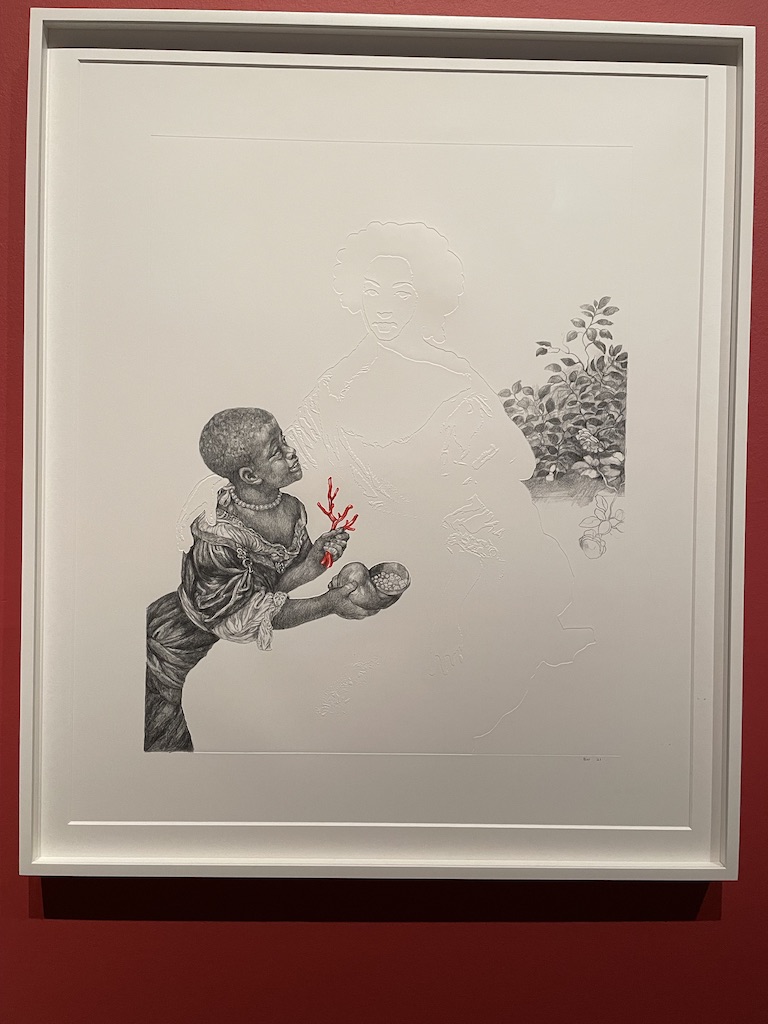

Here are just a few more of the pictures which caught my eye. A really, really great show. it’s on until 13th October 2024 at Tate Britain.