The Hay Wain is such a familiar image and conjures thoughts of ‘Merrie England’, the countryside fantasy of rural beauty, a simple life and the contented relationship between people who till the earth and the beauty of the fields where they work. At the press preview, listening to curator Christine Riding, it was fascinating to hear the context of the Hay Wain explained and then illustrated by a charming selection of complementary paintings, drawings, sketches and cartoons.

Took a couple of close-ups of the Hay Wain. It’s one of John Constable’s ‘six-footers’, a very large painting which was started in 1819 with the intention of grabbing the attention of collectors and fellow artists. Size does matter when you’re competing with other people to gain a reputation in the art work; this was an epic work, produced in his studio, but very much based on sketches and paintings made ‘en plein air’ in the Suffolk countryside Constable knew so well.

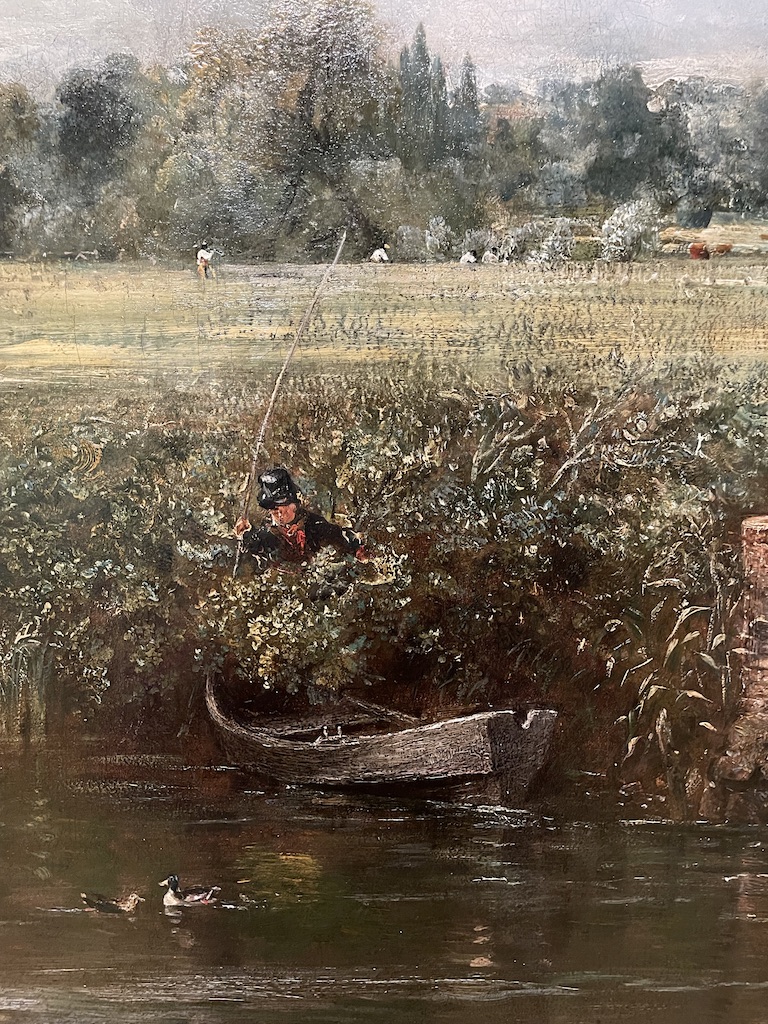

This is a large-scale (6ft) dry run which Constable painted. I love the liveliness and free painting. He does not become bogged down in detail yet all the elements of the composition are there.

On the left is a work by Constable entitled The Wheat Field. It makes rural life look very clean, romantic and relaxed. On the right is Golding Constable’s Kitchen Garden (his father) which was very personal to Constable and he kept it for himself and it was never sold in his lifetime.

This painting is by Thomas Gainsborough (1748) Like Constable, he was born and brought up in Suffolk and was familiar with the same landscape. This work depicts Cornard Wood, common land at the time. The painting belonged to Constable’s uncle, David Pike Watts and would have been familiar to the young artist as he was developing his interest in landscape painting and admiring Gainsborough’s technique.

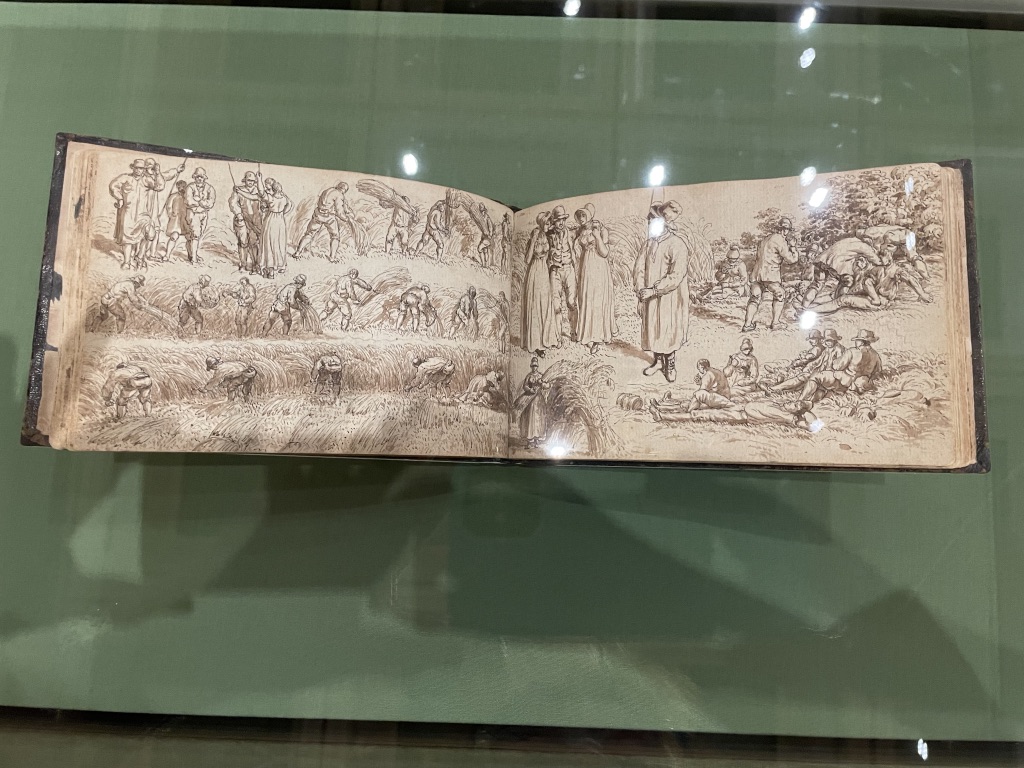

Always wonderful to see an artist’s sketch book and this shows how Constable studied field-workers and rural activity. On the right is a tiny oil sketch showing the composition of the Hay Wain. We learned that the house on the left, known as Willy Lott’s Cottage was, in fact, owned by Mr William Lott and it was a house, and a substantial dwelling. Perhaps Constable is guilty of loading his seminal work with a dose of sentimentality in order to appeal to the ideal of the rural idyll?

This is very charming set of tiny models depicting the best singers in the East Bergholt church choir. It has been attributed to the young John Constable as creator but we can’t be sure. They are very enchanting, tiny carved and painted wooden figures.

The show is just wonderful. It’s part of the National Gallery’s 200th year celebration and well worth a visit.