The works of Turner and Constable must be amongst some of the most recognised images in art history. Say the words Flatford Mill or A misty sunset in Venice and most of us will conjure the familiar bucolic image of a Suffolk Mill with a horse and cart or the beauty of Venice seen through a haze of cloud and watery sunshine. These works are amazing. But the history of these two artists is more entwined and their approach more similar than I had realised. This show, entitled Rivals and Originals, charts their artistic development as contemporaries and adversaries.

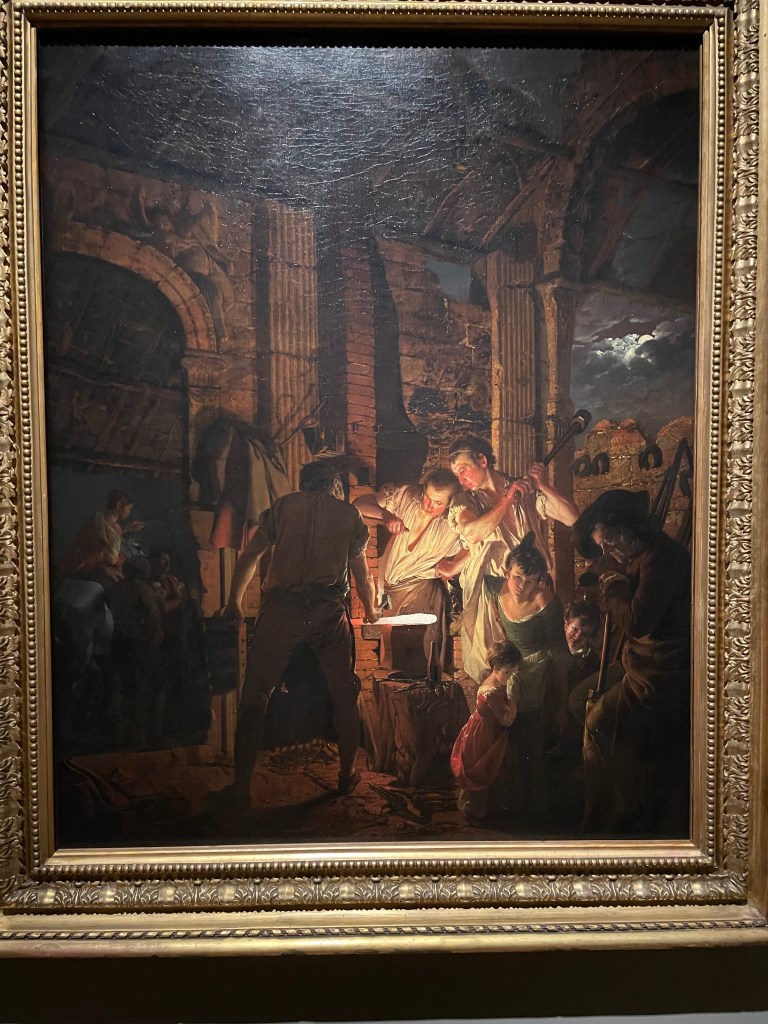

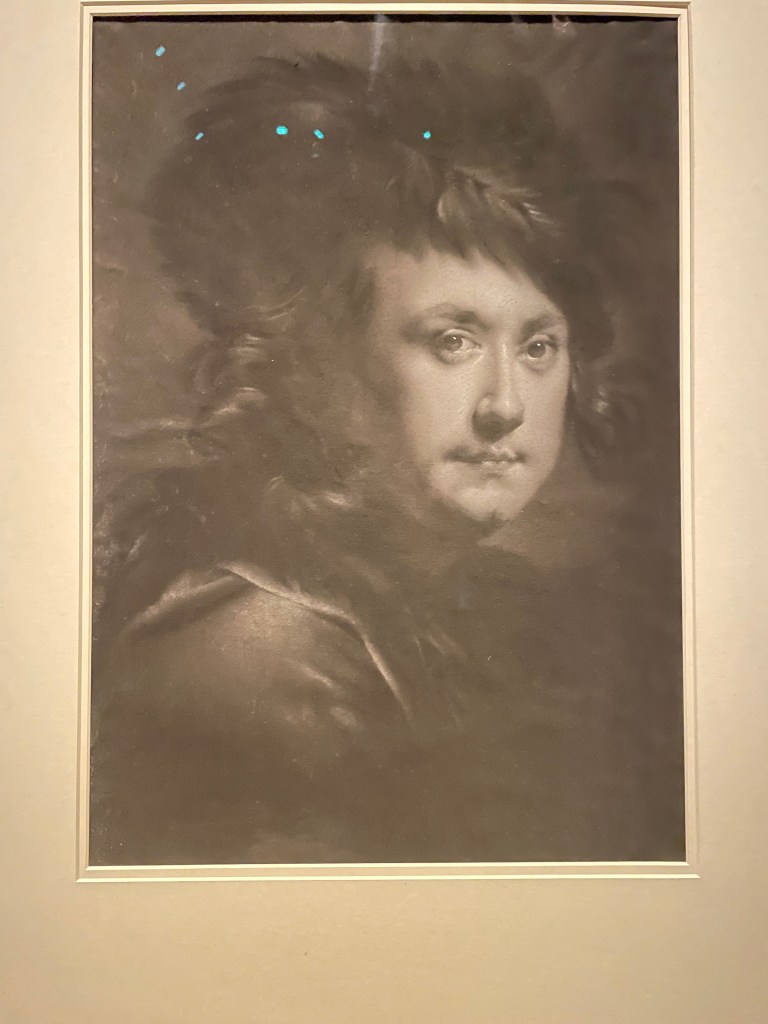

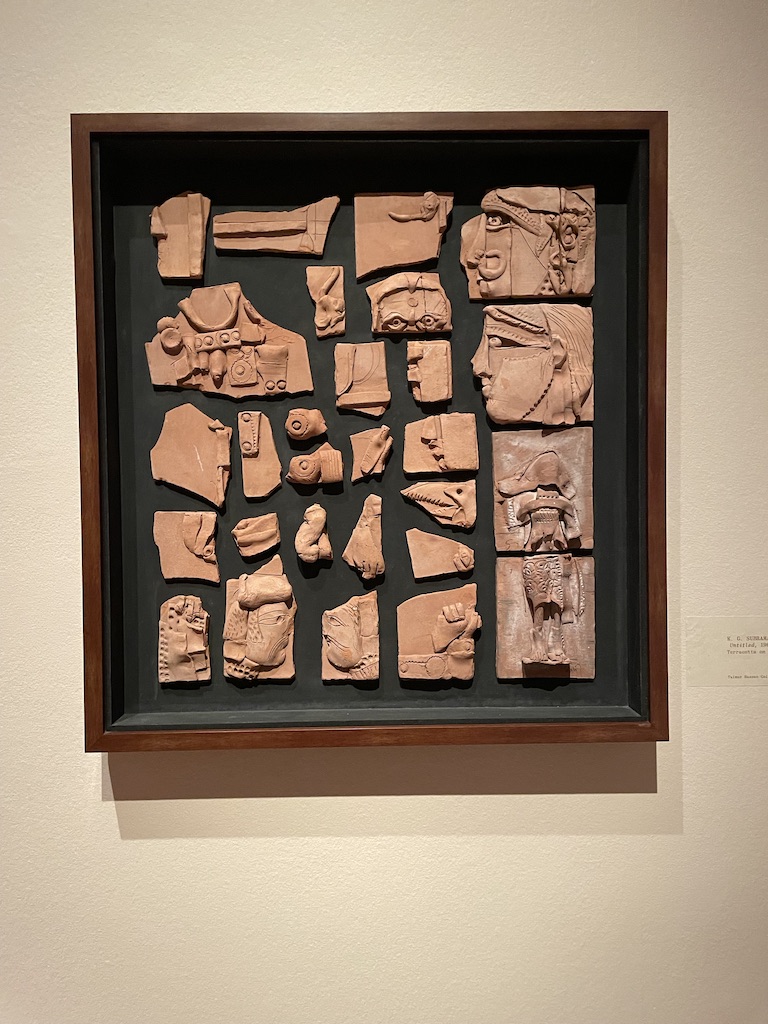

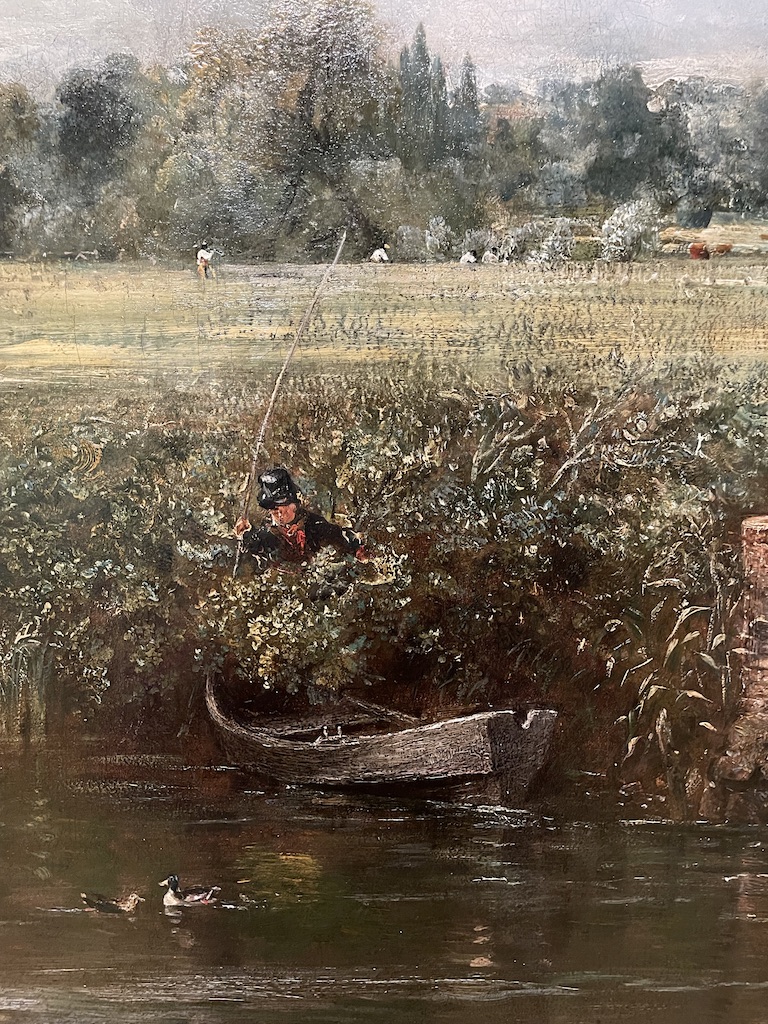

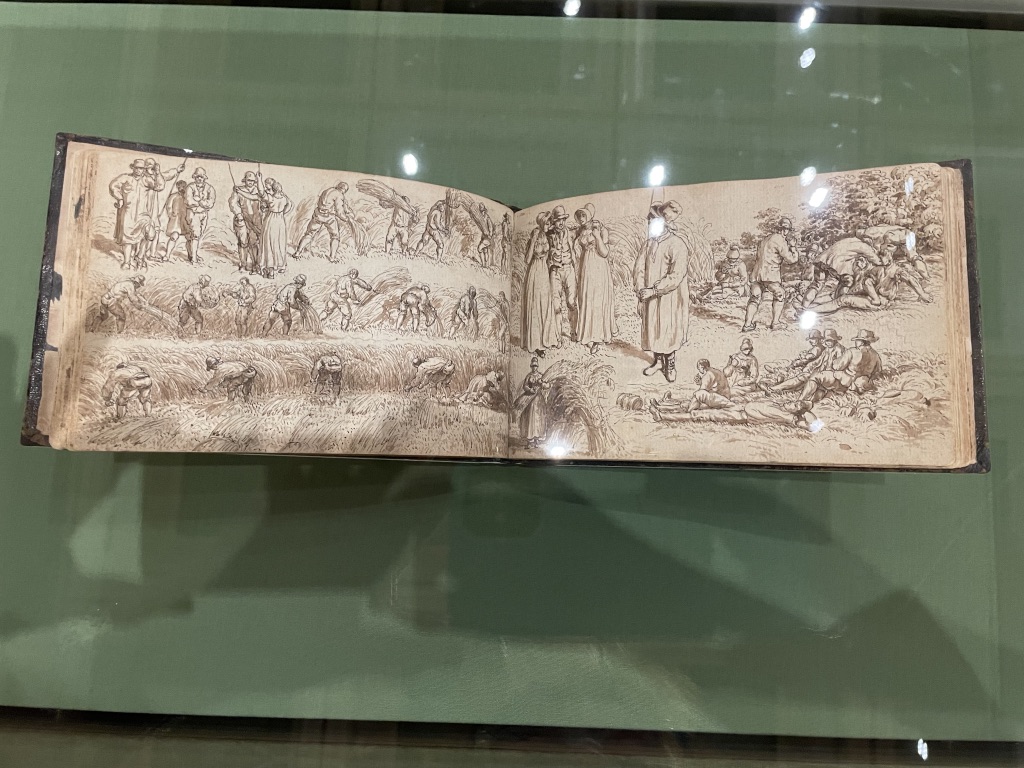

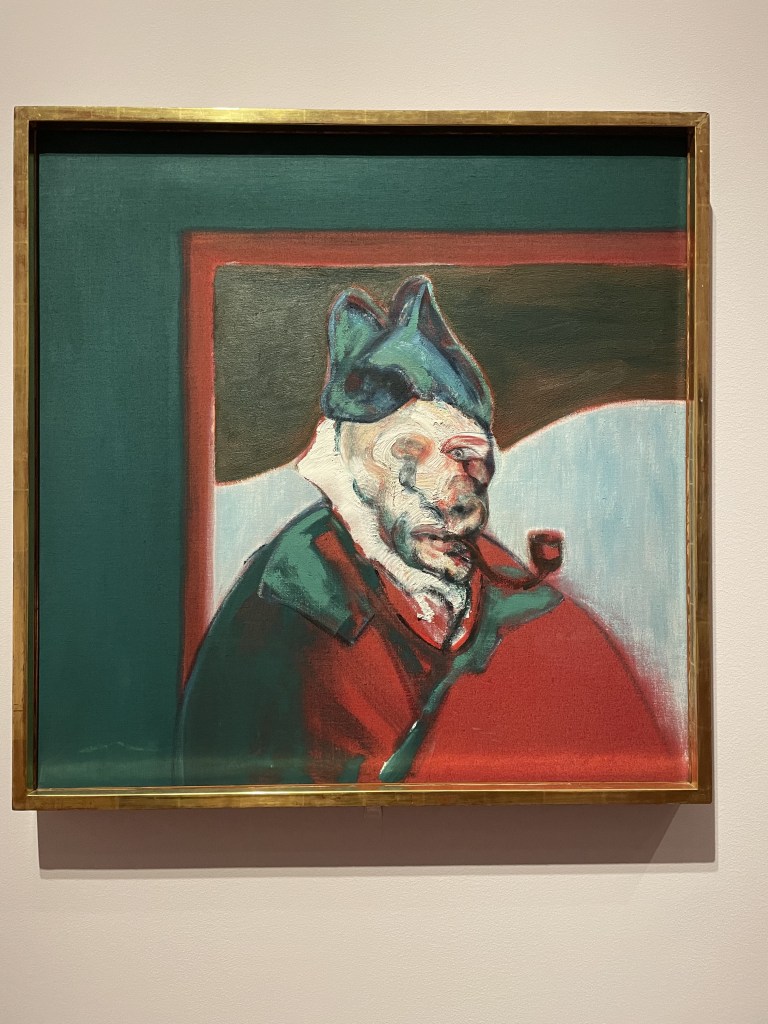

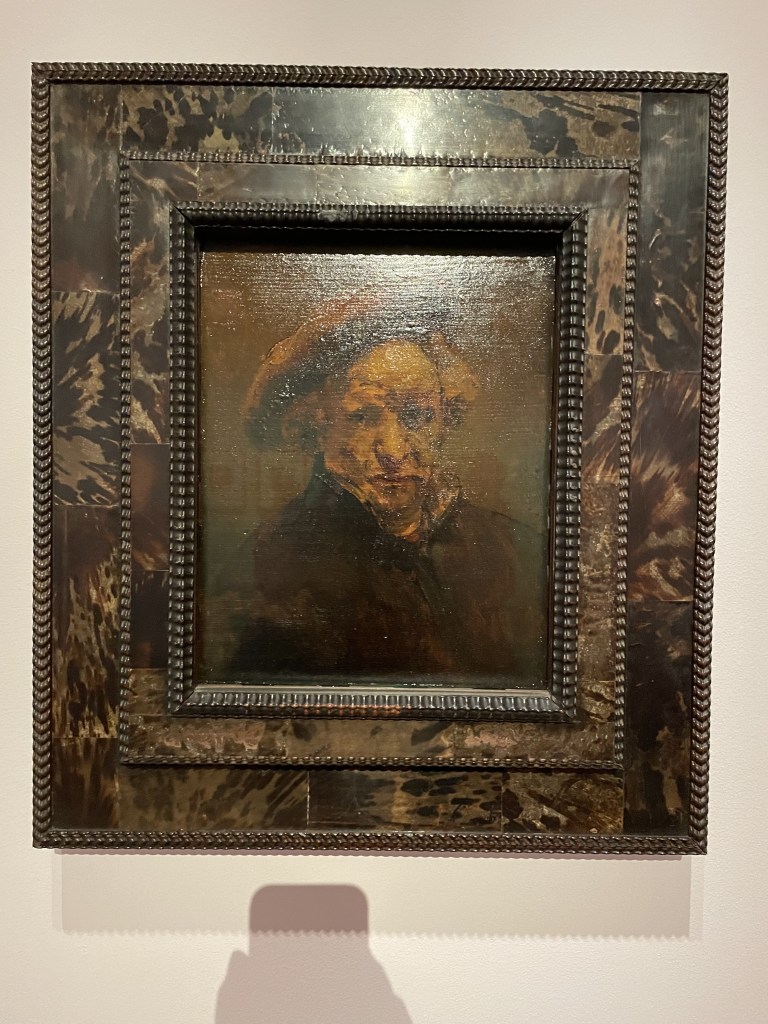

Both Turner and Constable were dedicated to art from an early age. Turner, you could argue, had the more difficult journey – the son of a barber based in Covent Garden, London, he demonstrated his skills at an early age and his father did his best to support his son’s desire to paint but he was not of the class expected to choose art as a career. Constable was born into middle class comfort in Suffolk and had to convince his family that he did not want to follow a conventional profession but devote his life to art. The pair developed their styles through study of Old Masters and a desire to push a narrative element into their art while recording contemporary life.

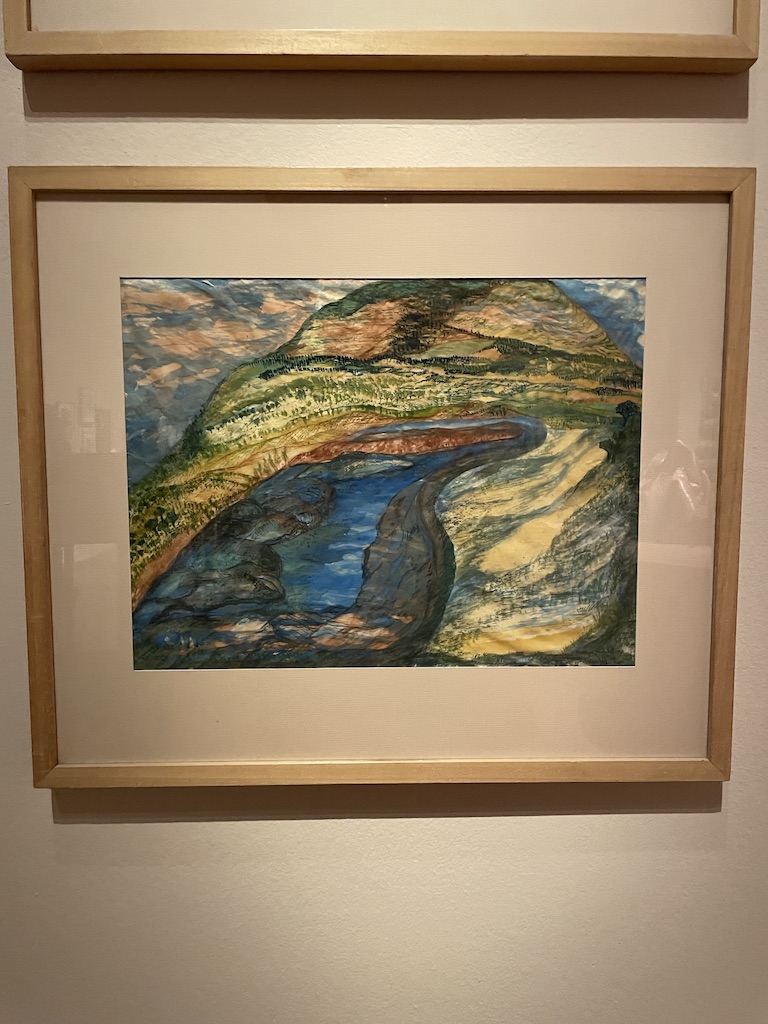

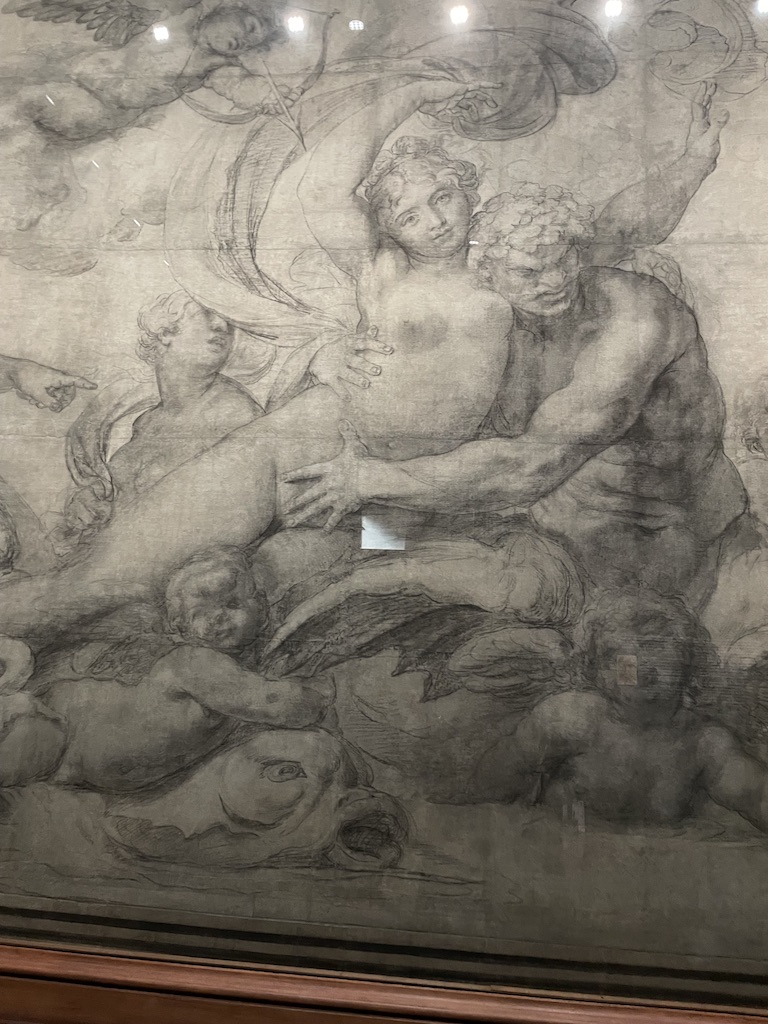

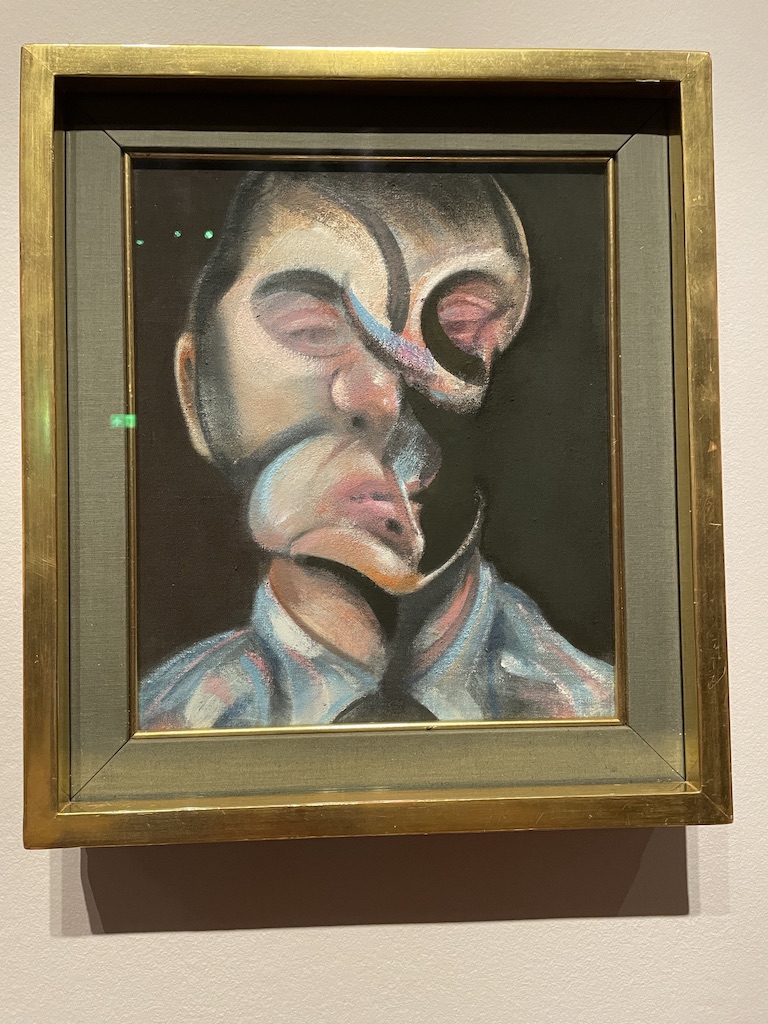

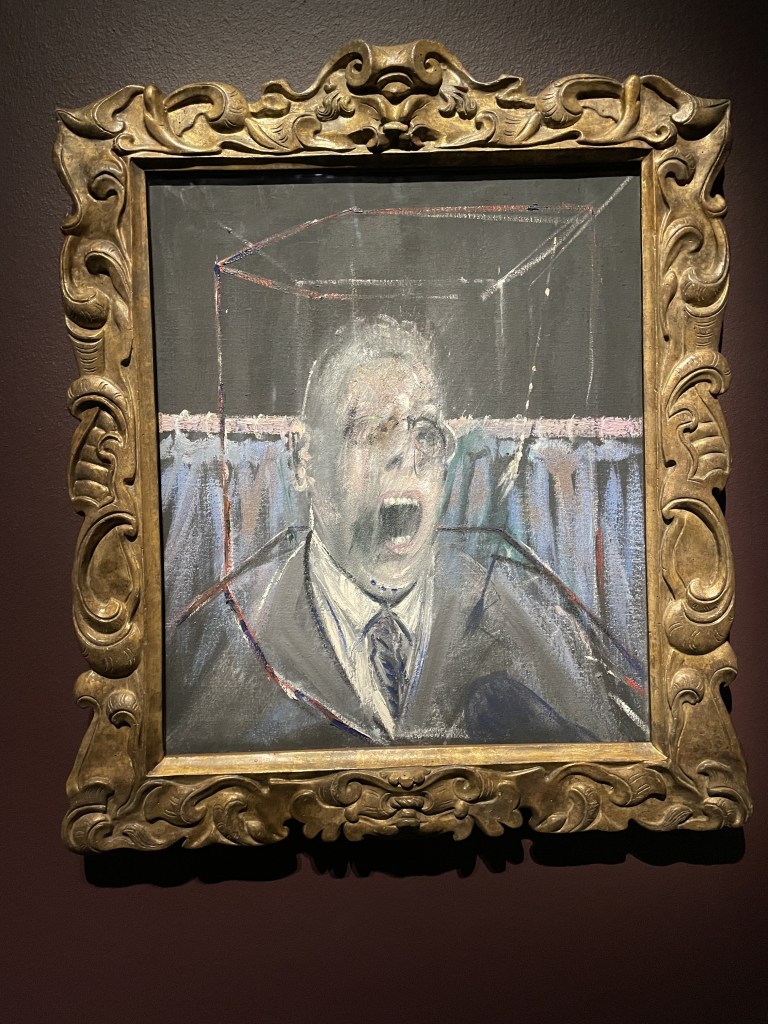

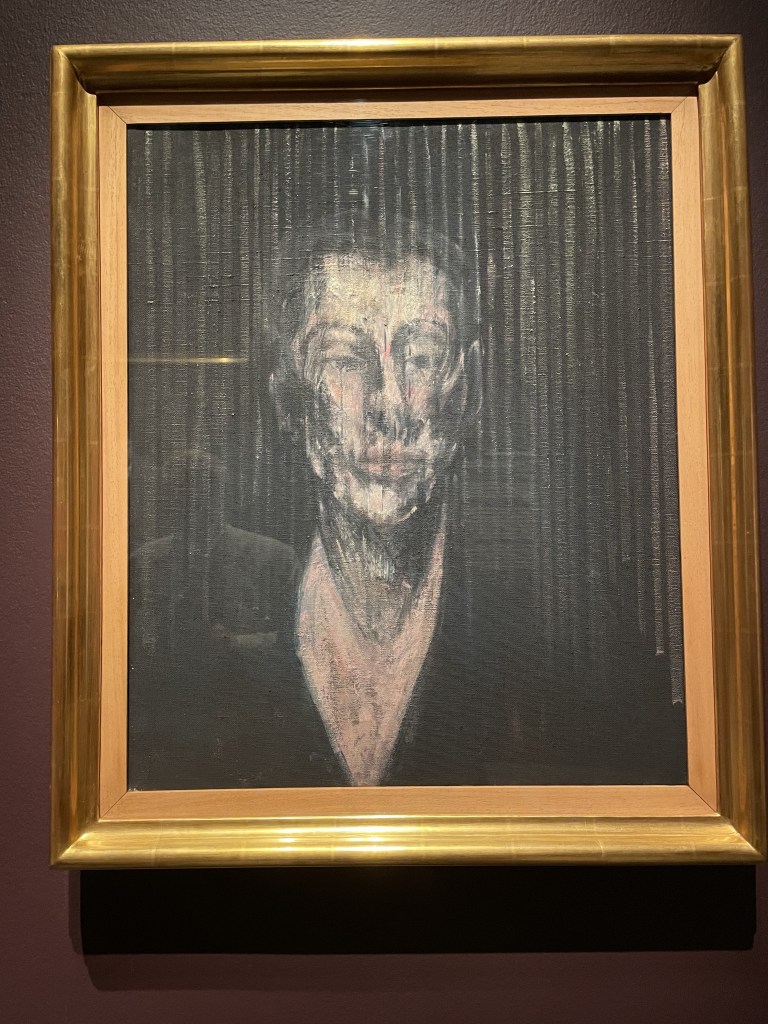

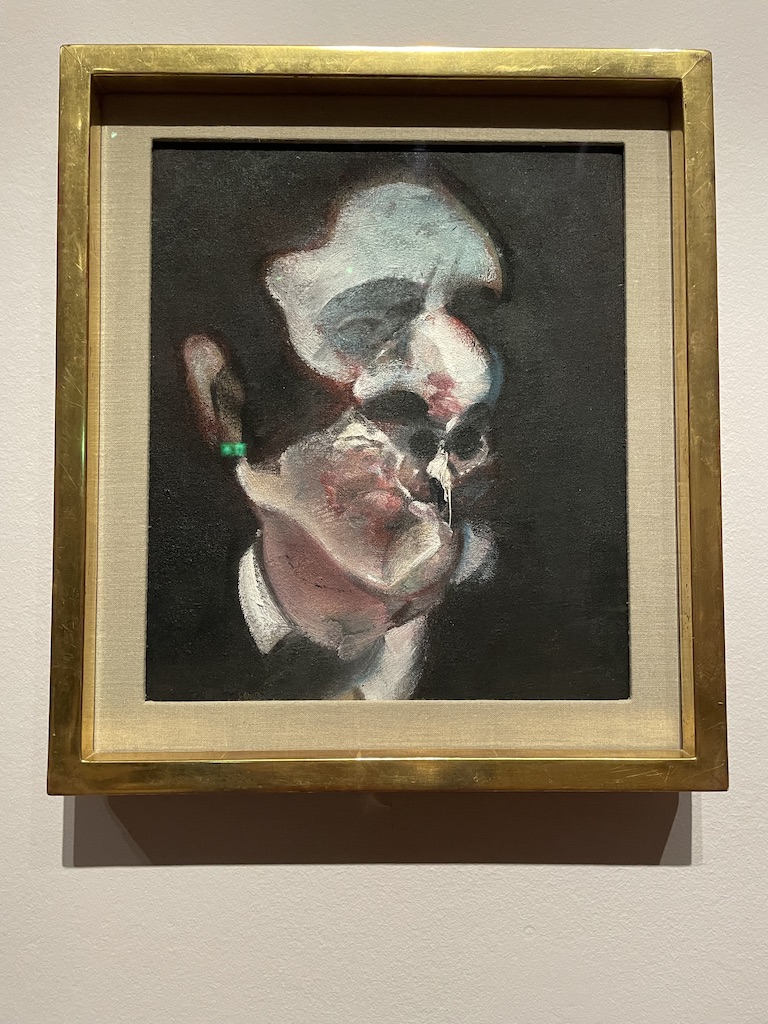

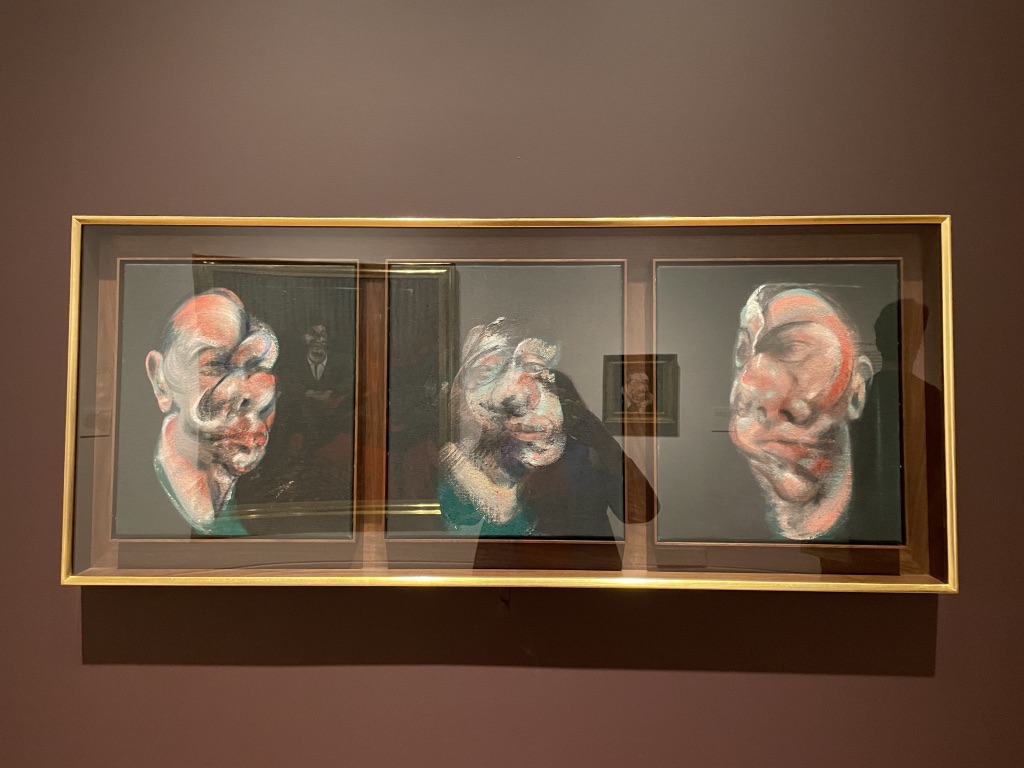

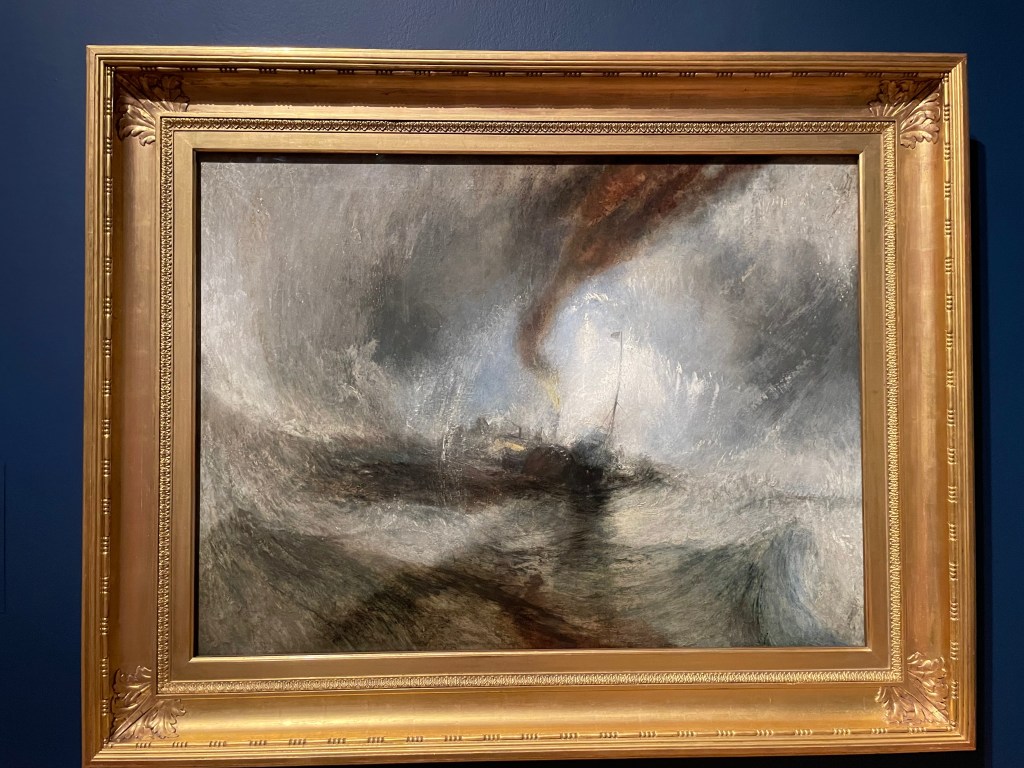

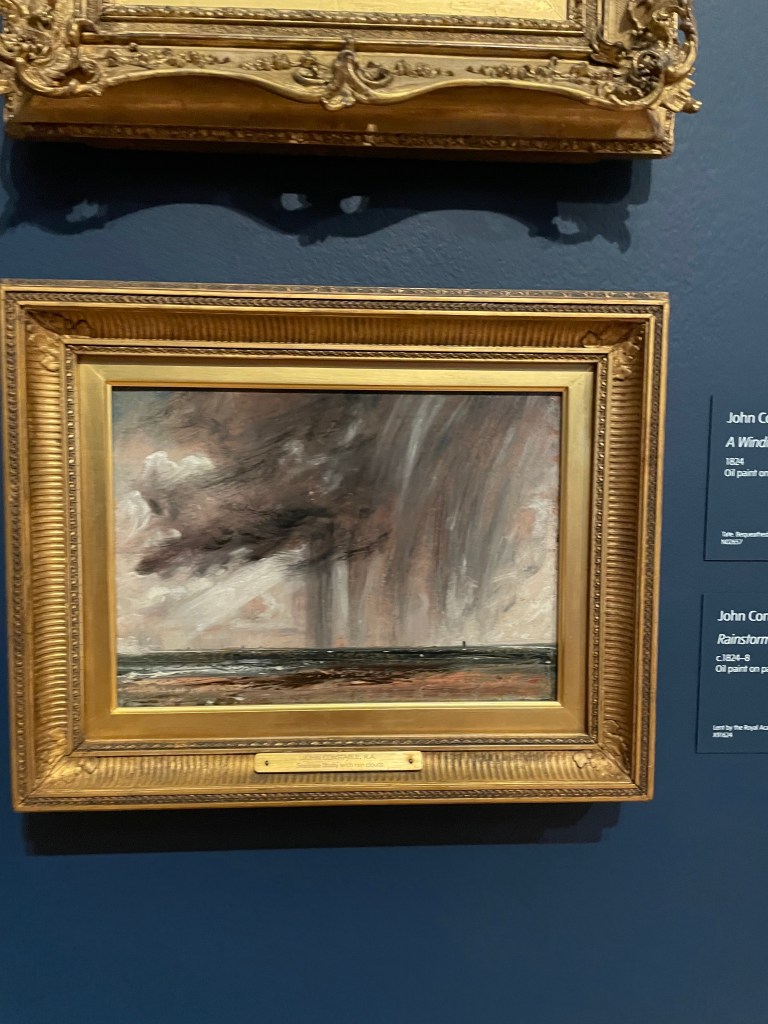

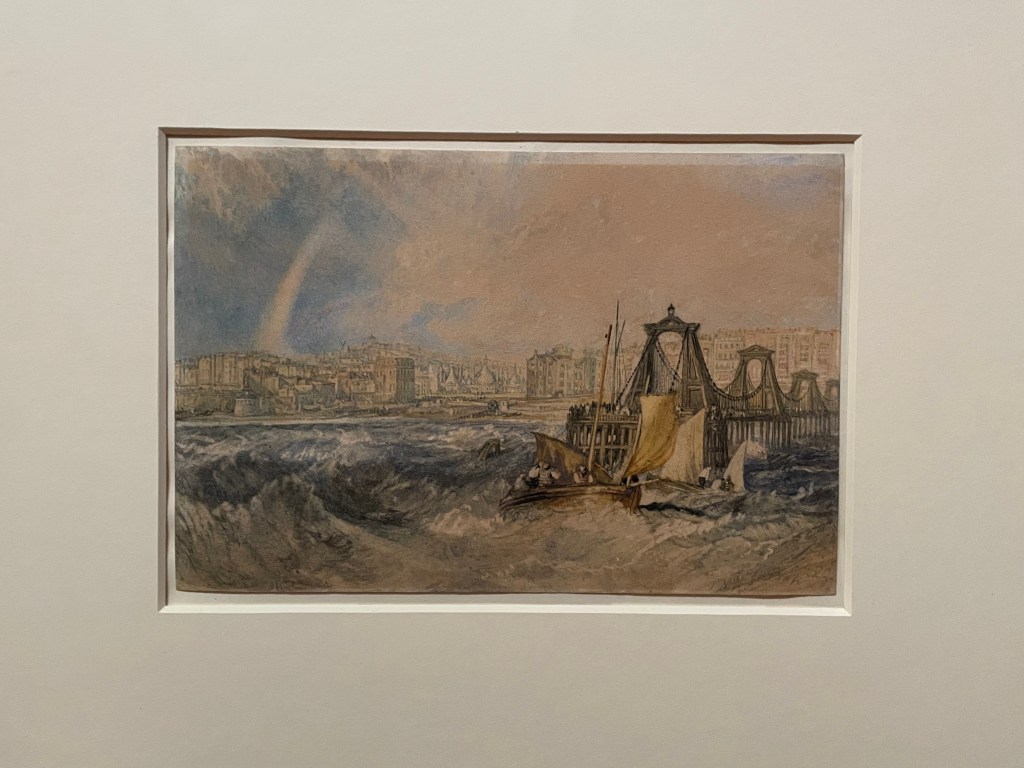

Sometimes it’s hard to differentiate between them – just look at these two, above. On the left is Turner’s Snow Storm – Steam-boat off a Harbour’s Mouth and on the right is Constable’s swift oil sketch called Rainstorm over the Sea. Both of them were fascinated by the power of nature and the constantly changing sky and weather conditions. They spent all their time sketching landscapes and painting the scene directly onto whatever surface they brought with them.

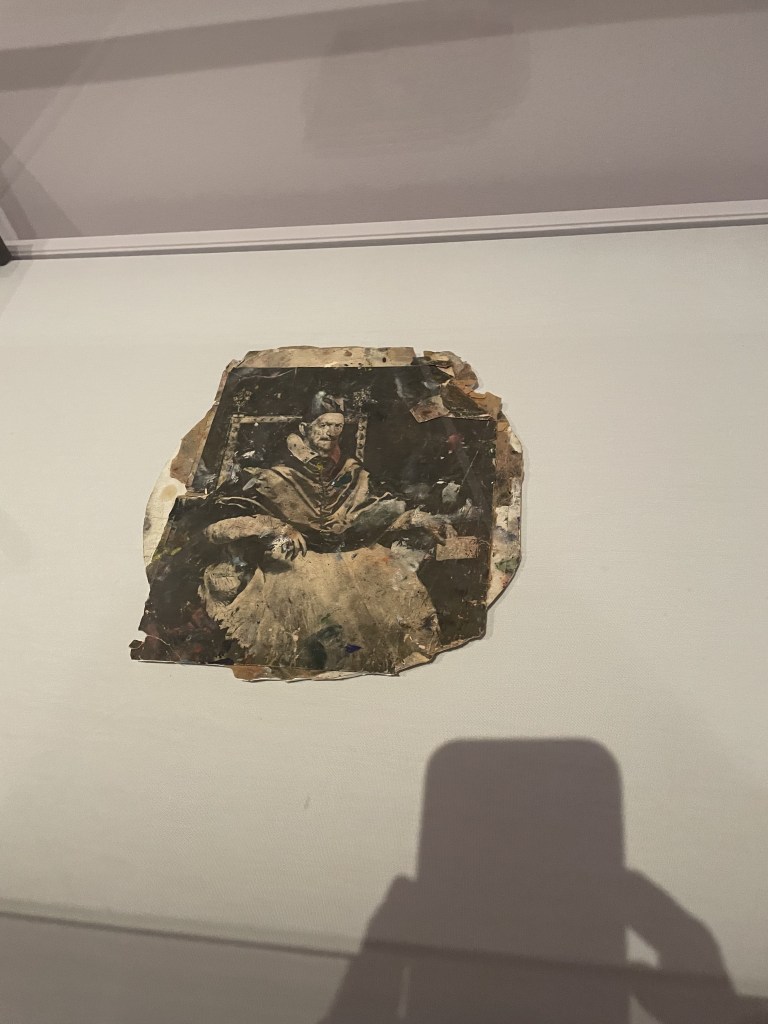

Both must have spent hours observing clouds in their infinite variety and using immediate sketches to dramatic effect. On the left is a selection of cloud studies by Constable and on the right is Turner’s massive painting Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps.

My takeaway from the show, apart from having thoroughly enjoyed it, was the chance to see the evolution of these two artists from detailed work, which might be as literal and accurate as possible, towards a much freer, expressive way of working. Both appear to have created their work at speed, using wonderful gestural swishes of paint or urgent daubs of white and black to denote drama and impact. They are both glorious. This is a wonderful show and well worth seeing.

It’s on at Tate Britain until 12 April 2026.